music.wikisort.org - Composer

Otto Nossan Klemperer (14 May 1885 – 6 July 1973) was a German-born orchestral conductor and composer, described as "the last of the few really great conductors of his generation."[1]

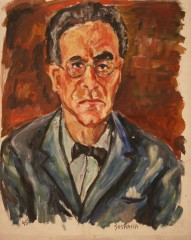

Otto Klemperer | |

|---|---|

Klemperer, circa 1920 | |

| Born | 14 May 1885 Breslau, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire (now Wrocław, Poland) |

| Died | 6 July 1973 (aged 88) Zürich, Switzerland |

| Citizenship | American (1940–1970) Israeli (1970–1973) |

| Occupation | Conductor, composer |

| Spouse(s) | Johanna Geisler (m. 1919) |

| Children | 2, including Werner Klemperer |

| Relatives | Victor Klemperer (cousin) |

Early life

Otto Klemperer was born in Breslau, Province of Silesia, in what was then the Imperial German state of Prussia; the city is now Wrocław, Poland.[2] His father Nathan Klemperer was originally from Josefov, the Jewish ghetto in the Bohemian city of Prague (now in the Czech Republic).[3] His mother was a Sephardic Jew from Hamburg.[3] Otto Klemperer studied music first at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, and later at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin under James Kwast and Hans Pfitzner. He followed Kwast to three institutions and credited him with the whole basis of his musical development. In 1905, he met Gustav Mahler while conducting the off-stage brass at a performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 2, Resurrection. He also made a piano arrangement of the second symphony.[4] Klemperer got the opportunity to present this work to Mahler in February 1907, on the occasion of the first of three trips to Vienna with Jacques van Lier. Mahler and Klemperer became friends, and Klemperer became conductor at the German Opera in Prague in 1907 on Mahler's recommendation.[5] Mahler wrote a short testimonial, recommending Klemperer, on a small card which Klemperer kept for the rest of his life. Later, in 1910, Klemperer assisted Mahler in the premiere of his Symphony No. 8, Symphony of a Thousand.

Music career

Klemperer went on to hold a number of positions, in Hamburg (1910–1912); in Barmen (1912–1913); the Strasbourg Opera (1914–1917); the Cologne Opera (1917–1924); and the Wiesbaden Opera House (1924–1927). From 1927 to 1931, he was conductor at the Kroll Opera in Berlin. In this post he enhanced his reputation as a champion of new music, playing a number of new works, including Janáček's From the House of the Dead, Schoenberg's Erwartung, Stravinsky's Oedipus rex, and Hindemith's Cardillac.

1930s move to United States

When the Nazi Party gained power in 1933, Klemperer left Germany shortly afterwards, first to Austria then to Switzerland.[2] He had previously converted to Catholicism,[6] but returned to Judaism at the end of his life. In 1935, he migrated to the United States, residing in California after being appointed music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.[2] While in Los Angeles, he began to concentrate more on the standard works of the Germanic repertoire that would later bring his greatest acclaim, particularly the works of Beethoven, Brahms and Gustav Mahler, though he gave the Los Angeles premieres of some of fellow Los Angeles resident Arnold Schoenberg's works with the Philharmonic. He also visited other countries, including the United Kingdom and Australia. While the orchestra responded well to his leadership, Klemperer had a difficult time adjusting to life and climate in Southern California, a situation exacerbated by repeated manic-depressive episodes, reportedly as a result of severe cyclothymic bipolar disorder. He also found that the dominant musical culture and leading music critics in the United States were largely unsympathetic to modern music from Weimar's Golden Age, and he felt both the music and his support of it were not properly appreciated.[7]

Klemperer hoped for a permanent position as principal conductor in New York or Philadelphia, but in 1936 he was passed over for both – first in Philadelphia, where Eugene Ormandy succeeded Leopold Stokowski at the Philadelphia Orchestra, and then in New York, where Arturo Toscanini's departure left a vacancy at the New York Philharmonic but John Barbirolli and Artur Rodziński were engaged in preference to Klemperer. The New York decision was particularly galling, as Klemperer had been engaged to conduct the first fourteen weeks of the New York Philharmonic's 1935–6 season, and Toscanini himself had suggested Klemperer as a possible replacement. Klemperer's bitterness at this decision was voiced in a letter he wrote to the Philharmonic's manager, Arthur Judson: "that the society did not reengage me is the strongest offense, the sharpest insult to me as artist, which I can imagine. You see, I am no youngster. I have a name and a good name. One could not use me in a most difficult season and then expell me. This non-reengagement will have very bad results not only for me in New York but in the whole world... This non-reengagement is an absolutely unjustified wrong done to me by the Philharmonic Society."[7][8]

Then, after completing the 1939 Los Angeles Philharmonic summer season at the Hollywood Bowl, Klemperer was visiting Boston and was diagnosed with a brain tumor; the subsequent surgery to remove "a tumour the size of a small orange" left him partially paralyzed. He went into a deep depression and was placed in an institution from which he escaped. The New York Times ran a cover story declaring him missing, and after he was found in New Jersey, a humiliating photo of him behind bars was printed in the Herald Tribune. Though he would occasionally conduct the Philharmonic after that, he lost the post of Music Director.[9] Furthermore, his erratic behavior during manic episodes made him an undesirable guest conductor of US orchestras, and the late flowering of his career centered in other countries. In 1940, Klemperer became a US citizen.[2]

1945 to 1950

After World War II, Klemperer helped found the Music Academy of the West summer conservatory in Santa Barbara,[10] before he returned to Europe to work at the Budapest Opera (1947–1950). Finding Communist rule in Hungary increasingly irksome, he became an itinerant conductor, guest conducting the Royal Danish Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and the Philharmonia of London.

The early 1950s

In the early 1950s, Klemperer experienced difficulties arising from his US citizenship. American union policies made it difficult for him to record in Europe, while his left-wing views made him increasingly unpopular with the State Department and FBI. In 1952, the US refused to renew his passport; in 1954, Klemperer returned to Europe and acquired a German passport.[7][11]

Recording for EMI/HMV

Klemperer's career was revitalized in 1954 by Walter Legge, the London-based record producer and founder/manager of the Philharmonia Orchestra. Legge engaged Klemperer to conduct the Philharmonia in performances of music by Beethoven (the complete symphonies cycle, some symphonies recorded several times), Brahms (complete symphonies et al.) and much more repertoire for EMI Records. Klemperer became the first principal conductor of the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1959. He settled in Switzerland at this time. He also appeared at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, sometimes stage-directing as well as conducting, as in a 1963 production of Richard Wagner's Lohengrin. Klemperer also conducted Mozart's Die Zauberflöte there in 1962.

A severe fall during a visit to Montreal in 1951 forced Klemperer to conduct seated in a chair. A severe burn, which resulted from his smoking in bed and trying to douse the flames with the contents of a bottle of alcohol, further paralyzed him. Through Klemperer's health issues, the tireless and unwavering support and assistance of his daughter Lotte, were crucial to his success.[12]

Final years

One of his last concert tours was to Jerusalem, a couple of years after the Six-Day War, at which time he was awarded an Israeli honorary passport.[13] Klemperer had performed in Israel before it became a state, and returned to Jerusalem only in 1970 to conduct the Israeli Broadcasting Authority Symphonic Orchestra in two concerts, performing the six Brandenburg Concertos of Bach, and Mozart's symphonies 39, 40 and 41. During this tour he took Israeli citizenship. He retired from conducting in 1971.

Klemperer died in Zürich, Switzerland, in 1973, aged 88, and was buried at Zürich's Jewish Cemetery Oberer Friesenberg, owned and provided for by the Jewish Religious Community of Zurich.[14]

He was an Honorary Member (HonRAM) of the Royal Academy of Music.

Composer

Klemperer is less well known as a composer, but like other famous conductors such as Furtwängler, Walter and Markevitch, he wrote a number of pieces, including six symphonies (only the first two were published), a Mass, nine string quartets, many lieder and the opera Das Ziel. He tried periodically to have his music performed, as he had hopes of being remembered as a composer as well as a conductor, but found little success. His works have generally fallen into neglect since his death, although commercial recordings of a few of his symphonic pieces have been issued.[15][16] Four of his string quartets and a selection of piano pieces and songs have been recorded in two limited edition CDs.[17]

Klemperer's recordings

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2018) |

Many listeners associate Klemperer with slow tempos, but recorded evidence shows that in earlier years his tempi could be quite a bit faster. For example, one of Klemperer's most noted performances was of Beethoven's Symphony No. 3, Eroica. Eric Grunin's Eroica Project contains tempo data on 363 recordings of the work from 1924 to 2007, and includes 10 by Klemperer – some recorded in the studio, most from broadcasts of live concerts. The earliest Klemperer performance on tape was recorded in concert in Cologne in 1954 (when he was 69 years old); the last was in London with the New Philharmonia Orchestra in 1970 (when he was 85). The passing years show a clear trend with respect to tempo: as Klemperer aged, he took slower tempi. In 1954, his first movement lasts 15:18 from beginning to end; in 1970 it lasts 18:41. In 1954 the main tempo of the first movement was about 135 beats per minute, in 1970 it had slowed to about 110 beats per minute. In 1954, the Eroica second movement, "Funeral March", had a timing of 14:35; in 1970, it had slowed to 18:51. Similar slowings took place in the other movements. Around 1954, Herbert von Karajan flew especially to hear Klemperer conduct a performance of the Eroica, and later he said to him: "I have come only to thank you, and say that I hope I shall live to conduct the Funeral March as well as you have done".

Similar, if less extreme, reductions in tempi can be noted in many other works for which Klemperer left multiple recordings, at least in recordings from when he was in his late 70s and his 80s. For example:

(a) Mozart's Symphony No. 38 Prague, another Klemperer specialty. In his concert recording from December 1950 (when he was 65 years old) with the RIAS Berlin Orchestra the timings are I. 9:45 (with repeat timing omitted; the performance actually does take the repeat); II. 7:45; and III. 5.24. In his studio March 1962 recording of the same work with the Philharmonia (recorded when he was 77 years old), the timings are notably slower: I. 10:53 (no repeat was taken); II. 8.58; III. 6:01. Unlike the late Eroica, the 1962 Prague is not notably slow; rather, the 1950 recording is much faster than most recordings of the work, even by "historically informed" conductors.

(b) Symphony No. 4 Romantic by Anton Bruckner (Haas edition with emendations). A 1947 concert recording with Concertgebouw Orchestra has timings of I. 14:03; II. 12:58; III. 10:11; and IV. 17.48. The EMI studio recording with the Philharmonia from 1963 has timings of I. 16:09; II; 14:00; III. 11.48; IV. 19:01. Again, the 1963 is not a notably slow performance, but the 1947 was quick. The March 1951 recording with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra was even quicker: I. 13:26; II. 11:56; III. 9:22; IV. 16:30.

(c) Symphony No. 7, Nachtlied (Song of the Night) by Gustav Mahler recorded for EMI in 1968. I. 27:43; II. 22:06; III. 10:27; IV. 15:41; V. 24:15. Klemperer's finale is particularly slow-paced at 24:15, where the average timing is approx. 17:30. Compare Klemperer's tempi with Sir Georg Solti for Decca (1971) at 16:29; James Levine for RCA (1982) at 17:45; Claudio Abbado for DG (2002) also at 17:45 and the Michael Tilson Thomas 2005 performance with the San Francisco SO at 18:05. "Thus, as you listen to this performance, it seems... to enclose you within its own world of evocative sound, a world that echoes... the world we may know, but remains a world transformed by imagination, remote, and complete within itself."[18]

Regardless of tempo, Klemperer's performances often maintain great intensity, and are richly detailed. Eric Grunin, in a commentary on the "opinions" page of his Eroica Project, notes: "....The massiveness of the first movement of the Eroica is real, but is not its main claim on our attention. That honor goes to its astonishing story (structure), and what is to me most unique about Klemperer is that his understanding of the structure remains unchanged no matter what his tempo... ". The German works of Kurt Weill were amongst Klemperer's favorites and he encouraged Weill to compose the orchestral suite Kleine Dreigroschenmusik.

Four years after his death, the First Movement from Klemperer's recording of Beethoven's 5th Symphony with the Philharmonia Orchestra was selected by NASA to be included on the Voyager Golden Record, a gold-plated copper record that was sent into space on the Voyager space craft. The record contained sounds and images which had been selected as examples of the diversity of life and culture on Earth.[19][20][21]

Discography

Klemperer made many recordings which are regarded as classics. Among the most noteworthy are:

| External audio | |

|---|---|

- Bach: St Matthew Passion with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Peter Pears, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig, and Walter Berry

- Bach: Mass in B minor

- Bach: Brandenburg Concertos with the Philharmonia Orchestra on ΕΜΙ

- Bartók: Viola Concerto (with William Primrose, and the Concertgebouw Orchestra, live version on Archiphon)

- Beethoven: Symphony cycles (notably the one from the mid-1950s on EMI)

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (recorded live, November 1957 and also in 1961)

- Beethoven: Fidelio (both the live recording from Covent Garden on Testament, and the studio EMI recording)

- Beethoven: Missa solemnis

- Beethoven: Piano Concertos Nos. 3–5, (with Claudio Arrau, live versions issued on Testament)

- Beethoven: Piano Concertos Nos. 1–5, (with Daniel Barenboim, on EMI)

- Brahms: Symphony cycles

- Brahms: Symphony No. 3, Philharmonia Orchestra, Columbia C90933, in 1957

- Brahms: Violin Concerto, with David Oistrakh

- Brahms: Ein deutsches Requiem, Philharmonia Orchestra with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, 1961 EMI recording

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 in E-flat Major

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 5 in B-flat Major, New Philharmonia Orchestra, march 1967 on Columbia SAX 5288

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A Major, New Philharmonia Orchestra, november 1964 on Columbia SMC 91437

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E Major, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, april 1957

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor with New York Philharmonic, 1934, and with New Philharmonia on EMI

- Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 1 with Claudio Arrau, live version issued on Music & Arts

- Franck: Symphony in D minor

- Handel: Messiah, with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Grace Hoffman, Nicolai Gedda, and Jerome Hines

- Haydn: Symphonies 88, 92, 95, 98, 100, 101, 102, 104

- Hindemith: Nobilissima Visione Suite (Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester, a 1954 version issued on Andante)

- Janáček: Sinfonietta (a 1951 Concertgebouw Orchestra live version, released by Archiphon)

- Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde, with Christa Ludwig and Fritz Wunderlich, New Philharmonia Orchestra, 1967 on EMI YAX 3282

- Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, "Resurrection", (1) – 1951 with Kathleen Ferrier & Jo Vincent; (2) – 1963 with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf & Hilde Rössel-Majdan

- Mahler: Symphony No. 4, Philharmonia Orchestra with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, 1961, on Columbia SAX 2441

- Mahler: Symphony No. 7, 1968

- Mahler: Symphony No. 9

- Mendelssohn: Symphonies Nos. 3-4

- Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 25 (with Daniel Barenboim)

- Mozart: Symphonies Nos. 25, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40 and 41

- Mozart: Don Giovanni (live version issued on Testament)

- Mozart: The Magic Flute, with Nicolai Gedda, Walter Berry, Gundula Janowitz, Lucia Popp, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as the First Lady

- Schoenberg: Verklärte Nacht (a 1955 live version with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, on Archiphon)

- Schubert: Symphonies 5, 8 (Unfinished) and 9. Philharmonia Orchestra (EMI)

- Schumann: Symphonies 1–4, with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Klemperer was the first to record them integrally

- Schumann: Piano Concerto (with Annie Fischer)

- Stravinsky: Petrushka

- Stravinsky: Pulcinella

- Stravinsky: Symphony in Three Movements

- Tchaikovsky: Symphonies Nos. 4, 5 and 6 with the Philharmonia Orchestra on EMI

- Wagner: Der fliegende Holländer (with Anja Silja)

- Wagner: Siegfried Idyll in the original chamber version with members of the Philharmonia Orchestra

- Weill: Kleine Dreigroschenmusik, 1931, 1967

Klemperer conducted his own Symphony No 2 in a 1970 EMI recording (ASD 2575) that also included his seventh string quartet.

A list of historical recordings of the Los Angeles Philharmonic with Klemperer conducting (including parts of the George Gershwin Memorial Concert at the Hollywood Bowl) can be found here: Otto Klemperer conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic

Klemperer's last recording, of Mozart's Serenade in E-flat, K.375, was made on 28 September 1971, the last time he conducted (apart from his conducting of a solitary movement from Beethoven's 7th Symphony in Munich on 6 September 1972, as mentioned above).

Personal life

In 1919, Klemperer married soprano Johanna Geisler.[22] They had two children, including Werner Klemperer, who became an actor.[12]

The diarist Victor Klemperer, who chronicled his life in the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany, was a cousin.[23]

References

Notes

- Keller, Hans; Cosman (1957). "Otto Klemperer". Musical Sketchbook. Oxford: Cassirer. OCLC 3225493.

- Brewer, Roy. "Otto Klemperer". allmusic. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Craft, Robert (31 October 1996). "Nights at the Opera". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Opera. Feb 1961, p 89

- Blyth, Alan. "Otto Klemperer talks to Alan Blyth (Gramophone, May 1978)". Gramophone. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Peter Heyworth (29 March 1996). Otto Klemperer, His Life and Times: 1885-1933. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-0-521-49509-7. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Joseph Horowitz, Review, The American Scholar, Spring 1997 (v.66, pp. 307-10)

- Peter Heyworth, Otto Klemperer: His Life and Times, Cambridge UP, Vols 1 and 2; 1996; ISBN 0521244889 ISBN 978-0521244886.

- Swed, Mark (31 August 2003). "The Salonen-Gehry Axis; The Los Angeles Philharmonic Has Arrived at a Rare Confluence of Musical Distinction and Visionary Architecture". Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles Times Magazine).

- Greenberg, Robert (26 August 2019). "Music History Monday: Lotte Lehmann". robertgreenbergmusic.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Peter Heyworth, Otto Klemperer: His Life and Times, Cambridge UP, Vols 1 and 2; 1996; ISBN 0521244889 ISBN 978-0521244886

- Martin Anderson (9 July 2003). "Lotte Klemperer". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "Maestro Chaslin talks about Klemperer and the tribute concert". The Classical Series (2012-13). Jerusalem Symphony. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "Berühmte Personen auf dem Friedhof der ICZ" (PDF). Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zürich - ICZ.

- Walton, Chris (2005). "CD Reviews: Klemperer, Symphony No. 1 et al". Tempo. 59 (232): 56–58. doi:10.1017/S0040298205260151. S2CID 144006408. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "Otto Klemperer – Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz • Alun Francis - Symphonies 1 & 2 • Four Symphonic Works". www.discogs.com. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- CDs catalogue numbers MACA001 and ok2b001

- RCM, High Fidelity Magazine, December 1969.

- "Voyager - Music on the Golden Record". voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- "Late Junction: The songs they sent to space". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- Sagan, Carl (2 April 2013). Murmurs of Earth. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-80202-6.

- "Klemperer, Otto, 1885-1973". SNA Cooperative. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Elon, Amos (24 March 1996). "The Jew Who Fought to Stay German". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2001. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

Sources

- Heyworth, Peter (1996). Otto Klemperer: His Life and Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56538-3.

- Holden, Raymond (2005). The Virtuoso Conductors: The Central European Tradition from Wagner to Karajan. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09326-8.

- Cosman, Milein (1957). Musical Sketchbook. Oxford: Bruno Cassirer. OCLC 3225493.

External links

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

- Otto Klemperer at AllMusic

- Beating Time: a play by Jim Grover about Klemperer

- The Stanford Collection. A comprehensive film archive, collected by Dr Charles Barber

- portrait of Otto Klemperer and Johanna Geisler by Nickolas Muray

- František Sláma – Archive Archived 14 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine. More on the history of the Czech Philharmonic between the 1940s and the 1980s: Conductors

- Newspaper clippings about Otto Klemperer in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

На других языках

[de] Otto Klemperer

Otto Klemperer (* 14. Mai 1885 als Otto Nossan Klemperer in Breslau; † 6. Juli 1973 in Zürich) war ein deutscher Dirigent und Komponist. Er zählt zu den großen Dirigenten des 20. Jahrhunderts.- [en] Otto Klemperer

[es] Otto Klemperer

Otto Klemperer (Breslavia, Imperio alemán (hoy en Polonia), 14 de mayo de 1885 - Zúrich, 6 de julio de 1973) fue un director de orquesta alemán.[ru] Клемперер, Отто

О́тто Кле́мперер (нем. Otto Klemperer, 14 мая 1885, Бреслау — 6 июля 1973, Цюрих) — немецкий дирижёр и композитор еврейского происхождения.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии