music.wikisort.org - Composition

"Louie Louie" is a rhythm and blues song written and composed by American musician Richard Berry in 1955, recorded in 1956, and released in 1957. It is best known for the 1963 hit version by the Kingsmen and has become a standard in pop and rock. The song is based on the tune "El Loco Cha Cha" popularized by bandleader René Touzet and is an example of Afro-Cuban influence on American popular music.

| "Louie Louie" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Richard Berry | ||||

| A-side | You Are My Sunshine[1][2] | |||

| Written | 1955 | |||

| Released | April 1957 | |||

| Recorded | 1956 | |||

| Studio | Hollywood Recorders | |||

| Genre | Rhythm and blues | |||

| Length | 2:09 | |||

| Label | Flip | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Richard Berry | |||

| Richard Berry singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Louie Louie" tells, in simple verse–chorus form, the first-person story of a Jamaican sailor returning to the island to see his lover.

Historical significance

The "remarkable historical impact"[3] of "Louie Louie" has been recognized by organizations and publications worldwide for its influence on the history of rock and roll. A partial list (see Recognition and rankings table below) includes the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Grammy Hall of Fame, National Public Radio, VH1, Rolling Stone Magazine, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Recording Industry Association of America. Other major examples of the song's legacy include the celebration of International Louie Louie Day every year on April 11; the annual Louie Louie Parade in Philadelphia from 1985 to 1989; the LouieFest in Tacoma from 2003 to 2012; the ongoing annual Louie Louie Street Party in Peoria; and the unsuccessful attempt in 1985 to make it the state song of Washington.

Dave Marsh in his book The History and Mythology of the World's Most Famous Rock 'n' Roll Song wrote, "It is the best of songs, it is the worst of songs",[4] and also called it "cosmically crude".[5] Music historian Peter Blecha noted, "Far from shuffling off to a quiet retirement, evidence indicates that 'Louie Louie' may actually prove to be immortal."[6] Rock critic Greil Marcus called it "a law of nature"[7] and New York Times music critic Jon Pareles, writing in a 1997 obituary for Richard Berry, termed it "a cornerstone of rock".[8] Other writers described it as "musically simple, lyrically simple, and joyously infectious",[9] "deliciously moronic",[10] "a completely unforgettable earworm",[11] and "the essence of rock's primal energy".[12] Others noted that it "served as a bridge to the R&B of the past and the rap scene of the future",[13] that "it came to symbolize the garage rock genre, where the typical performance was often aggressive and usually amateurish",[14] and that "all you need to make a great rock 'n' roll record are the chords to 'Louie Louie' and a bad attitude."[15] Humorist Dave Barry (perhaps with some exaggeration) called it "one of the greatest songs in the history of the world".[16]

The Kingsmen's recording was the subject of an FBI investigation about the supposed, but nonexistent, obscenity of the lyrics that ended without prosecution.[17] The nearly unintelligible (and innocuous) lyrics were widely misinterpreted, and the song was banned by radio stations. Marsh wrote that the lyrics controversy "reflected the country's infantile sexuality" and "ensured the song's eternal perpetuation",[18] while another writer termed it "the ultimate expression of youthful rebellion".[19] Jacob McMurray in Taking Punk To The Masses noted, "All of this only fueled the popularity of the song ... imprinting this grunge ur-message onto successive generations of youth, ... all of whom amplified and rebroadcast its powerful sonic meme ...."[20]

Original version by Richard Berry and the Pharaohs

Richard Berry was inspired to write the song in 1955 after listening to an R&B interpretation of "El Loco Cha Cha" performed by the Latin R&B group Ricky Rillera and the Rhythm Rockers.[21] The tune was written originally as "Amarren Al Loco" ("Tie Up the Madman") by Cuban bandleader Rosendo Ruiz Jr., also known as Rosendo Ruiz Quevedo, but became best known in the "El Loco Cha Cha" arrangement by René Touzet which included a ten-note "1-2-3 1–2 1-2-3 1–2" tumbao or rhythmic pattern.[22][23]

In Berry's mind, the words "Louie Louie" "just kind of fell out of the sky",[21] superimposing themselves over the repeating bassline. Lyrically, the first person perspective of the song was influenced by "One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)," which is sung from the perspective of a customer talking to a bartender ("Louie" was the name of Berry's bartender).[24] Berry cited Chuck Berry's "Havana Moon" and his exposure to Latin American music for the song's speech pattern and references to Jamaica.[25]

Los Angeles-based Flip Records recorded Berry's adaptation with his vocal group the Pharaohs in 1956 and released it in April 1957 as a single B-side of "You Are My Sunshine".[26] The Pharaohs were Godoy Colbert (first tenor), Stanley Henderson (second tenor, subbing for Robert Harris), and Noel Collins (baritone). Gloria Jones of the Dreamers provided additional backup vocals. Session musicians included Plas Johnson on tenor sax, Jewel Grant on baritone sax, Ernie Freeman on piano, Irving Ashby on guitar, Red Callender on bass, Ray Martinez on drums, and John Anderson on trumpet.[27][28]

Just prior to the song's release, Berry sold his portion of the publishing and songwriting rights for "Louie Louie" and four other songs for $750 to Max Feirtag, the head of Flip Records, to raise cash for his upcoming wedding.[21][29] The single was a regional hit on the West Coast, particularly in San Francisco, and when Berry toured the Pacific Northwest, local R&B bands began to play the song, increasing its popularity. The song was re-released by Flip in 1961 as an A-side single and again in 1964 on a four-song EP, but never appeared on any of the various record charts. The label reported that the single had sold 40,000 copies.

Other versions appeared on Casino Club Presents Richard Berry (1966), Great Rhythm and Blues Oldies Volume 12 (1977), The Best of Louie, Louie (1983), and In Session: Great Rhythm & Blues (2002). Although similar to the original, the version on Rhino's 1983 The Best of Louie, Louie compilation[30] is actually a note-for-note re-recording (with backup vocals by doo wop revival group Big Daddy)[31] created because licensing could not be obtained for Berry's 1957 version.[32][7] The original version was not legitimately re-released until the Ace Records Love That Louie compilation in 2002.[33]

While the title of the song is often rendered with a comma ("Louie, Louie"), in 1988, Berry told Esquire magazine that the correct title of the song was "Louie Louie" with no comma.[21]

Cover versions

"Louie Louie" is the world's most recorded rock song, with published estimates ranging from over 1,600[6] to more than 2,000.[34] It has been released or performed by a wide range of artists from reggae to hard rock, from jazz to psychedelic, from hip hop to easy listening. Peter Doggett labeled it "almost impossible to play badly"[35] and Greil Marcus proclaimed, "Has there ever been a bad version of 'Louie Louie'?"[36]

The Kingsmen version in particular has been cited as the "rosetta stone" of garage rock,[37] the defining "ur-text" of punk rock,[38][39] and "the original grunge classic".[40] "The influential rock critics Dave Marsh and Greil Marcus believe that virtually all punk rock can be traced back to a single proto-punk song, 'Louie Louie'."[41]

1950s

Richard Berry was on the underbill for a concert in the Seattle-Tacoma area in September 1957 and his record appeared on local radio station charts in November 1957.[42] Local R&B groups like Ron Holden and the Playboys and the Dave Lewis Combo popularized "Louie Louie", rearranging Berry's version and performing it at live shows and "battle of the bands" events.[43][44]

Holden recorded an unreleased version, backed by the Thunderbirds, for the Nite Owl label in 1959.[45] As a leader of the "dirty but cool" Seattle R&B sound,[46] he would often substitute mumbled, "somewhat pornographic" lyrics in live performances.[47] Lewis, "the singularly most significant figure on the Pacific Northwest's nascent rhythm & blues scene in the 1950s and 1960s",[48] released a three chord clone, "David's Mood - Part 2", that was a regional hit in 1963.

The Wailers, Little Bill and the Bluenotes, the Frantics, Tiny Tony and the Statics, Merrilee and the Turnabouts, and other local groups soon added the song to their set lists.[49]

1960s

Rockin' Robin Roberts and the Wailers (1961)

| "Louie Louie" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Rockin' Robin Roberts | |

| B-side | "Maryanne" |

| Released | 1961 |

| Recorded | 1960 |

| Genre |

|

| Length | 2:40 |

| Label | Etiquette |

Robin Roberts developed an interest in rock 'n' roll and rhythm and blues records as a high school student in Tacoma, Washington. Among the songs he began performing as an occasional guest singer with a local band, the Bluenotes, in 1958 were "Louie Louie", which he had heard on Berry's obscure original single, and Bobby Day's "Rockin' Robin", which gave him his stage name.[50]

In 1959, Roberts left the Bluenotes and began singing with another local band, the Wailers, famed for their "hard-nosed R&B/rock fusion".[51] Known for his dynamic onstage performances, Roberts added "Louie Louie" to the band's set and, in 1960 recorded the track with the Wailers as his backing band.[52] The arrangement, devised by Roberts with the band, was "the first-ever garage version of 'Louie Louie'"[52] and included his ad-lib "Let's give it to 'em, RIGHT NOW!!" Released as a single on the band's own label, Etiquette, in early 1961, it became a huge hit locally, charting at No. 1 on Seattle's KJR and establishing "Louie Louie" as "the signature riff of Northwest rock 'n' roll".[53] It also picked up play across the border in Vancouver, British Columbia, appearing in the top 40 of the CFUN chart. The popularity of the Roberts release effectively buried another version put out at about the same time by Little Bill Englehardt (Topaz T-1305).[52]

The record was then reissued and promoted by Liberty Records in Los Angeles, but it failed to chart nationally.[54] The track was included on the 1963 album The Wailers & Co, the 1964 compilation album Tall Cool One, the 1998 reissue of the 1962 album The Fabulous Wailers Live at the Castle, and multiple later compilations.[55]

Roberts was killed in an automobile accident in 1967, but his "legacy would reverberate down through the ages".[53] Dave Marsh dedicated his 1993 book, "For Richard Berry, who gave birth to this unruly child, and Rockin' Robin Roberts, who first raised it to glory."[56]

The Kingsmen (1963)

| "Louie Louie" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Original release | ||||

| Single by the Kingsmen | ||||

| from the album The Kingsmen in Person | ||||

| B-side | "Haunted Castle" | |||

| Released | June 1963 (Jerden) October 1963 (Wand) | |||

| Recorded | April 6, 1963 | |||

| Genre | Garage rock[57] | |||

| Length | 2:42 | |||

| Label | Jerden | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| The Kingsmen singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Wand Re-issue | ||||

Second Wand release with "Lead vocal by Jack Ely" text | ||||

On 6 April 1963,[58] the Kingsmen, a rock and roll group from Portland, Oregon, chose "Louie Louie" for their second recording, their first having been "Peter Gunn Rock". The Kingsmen recorded the song at Northwestern Inc. Motion Pictures & Recording Studios at 411 SW 13th Avenue in Portland, Oregon. The one hour session cost either $36,[59] $50,[60] or somewhere in between[61] and the band split the cost.[62]

The session was produced by Ken Chase, a local disc jockey on the AM rock station 91 KISN who also owned the teen nightclub that hosted the Kingsmen as their house band. The engineer for the session was the studio owner, Robert Lindahl. The Kingsmen's lead vocalist, Jack Ely, based his version on the recording by Rockin' Robin Roberts with the Fabulous Wailers, but unintentionally reintroduced Berry’s original rhythm as he showed the other members how to play it with a 1–2–3, 1–2, 1–2–3 beat instead of the 1–2–3–4, 1–2, 1–2–3–4 beat on the Wailers record.[63] The night before their recording session, the band played a 90-minute version of the song during a gig at a local teen club. The Kingsmen's studio version was recorded in one partial and one full take.[64] They also recorded "Jamaica Farewell" and what became the B-side of the release, an original "surf instrumental"[65] by Ely and keyboardist Don Gallucci called "Haunted Castle".[61] Jerry Dennon’s local Jerden label pressed 1,000 copies.[66]

A significant error on the Kingsmen version occurs just after the lead guitar break. As the group was going by the Wailers version, which has a brief restatement of the riff twice over before the lead vocalist comes back in, it would be expected that Ely would do the same. Ely, however, missed his mark, coming in two bars too soon, before the restatement of the riff. He realized his mistake and stopped the verse short, but the band did not realize that he had done so. As a quick fix, drummer Lynn Easton covered the pause with a drum fill. The error is now so well known that multiple versions by other groups duplicate it.[67][68]

The Kingsmen's version with its "ragged",[69] "chaotic",[70] "shambolic, lumbering style",[71] complete with "manic lead guitar solo, insane cymbal crashes, generally slurred and unintelligible lyrics",[72] transformed the earlier Rockin' Robin Roberts version on which it was based into a "gloriously incoherent",[73] "raw and raucous"[67] romp. Ely had to stand on tiptoe to sing into a boom mike, and his braces further impeded his singing. The guitar break is triggered by a shout, "Okay, let's give it to 'em right now!", both lifted from the Roberts version.[74] Critic Dave Marsh suggests it is this moment that gives the recording greatness: "[Ely] went for it so avidly you'd have thought he'd spotted the jugular of a lifelong enemy, so crudely that, at that instant, Ely sounds like Donald Duck on helium. And it's that faintly ridiculous air that makes the Kingsmen's record the classic that it is, especially since it's followed by a guitar solo that's just as wacky."[75] Marsh ranked the song as No. 11 out of the 1001 greatest singles ever made, describing it as "the most profound and sublime expression of rock and roll's ability to create something from nothing".[76] In Rock and Roll: An Introduction, Michael Campbell notes, "The greater freedom of the rhythm section and a blues-influenced guitar solo style were among the features that distinguish rock from the music that came before it. Their use by the Kingsmen shows that they were becoming common practice."[77]

First released in May 1963, the single was initially issued by the small Jerden label, before being picked up by the larger Wand Records (after a pass by Herb Alpert's A&M Records)[78] and released in October 1963. Sales of the Kingsmen record were initially so low (reportedly 600) that the group considered disbanding. Things changed when Boston's biggest DJ, Arnie Ginsburg, was given the record by a pitchman. Amused by its slapdash sound, he played it on his program as "The Worst Record of the Week". Despite the slam, listener response was swift and positive.[79]

By the end of October, it was listed in Billboard as a regional breakout and a "bubbling under" entry for the national chart. Meanwhile, the Raiders version, with far stronger promotion, was becoming a hit in California and was also listed as "bubbling under" one week after the Kingsmen debuted on the chart. For a few weeks, the two singles appeared destined to battle each other, but demand for the Kingsmen single, backed by national promotion from Wand Records, acquired momentum and by the end of 1963, Columbia Records had stopped promoting the Raiders version.

It entered the top ten on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for December 7, and peaked at No. 2 the following week, a spot which it held for six non-consecutive weeks; it would remain in the top 10 throughout December 1963 and January 1964 before dropping off in early February.[80] In total, the Kingsmen's version spent 16 weeks on the Hot 100, selling a million copies by April 1964.[81] "Dominique" by the Singing Nun and "There! I've Said It Again" by Bobby Vinton prevented the single from reaching No. 1 (although Marsh asserts that it "far outsold" the other records, but was denied Billboard's top spot due to lack of "proper decorum".)[82] "Louie Louie" did reach No. 1 on the Cashbox and Music Vendor/Record World pop charts, as well as No. 1 on the Cashbox R&B chart.[83] It was the last No. 1 on Cashbox before Beatlemania hit the United States with "I Want to Hold Your Hand".[84] The Kingsmen version quickly became a standard at teen parties in the U.S. during the 1960s and, reaching No. 26 on the UK Singles Chart,[85] was the preferred tune for a popular British dance called "The Shake".[86] The first album, The Kingsmen In Person, peaked at No. 20 in 1964 and remained on the charts for over two years (131 weeks total) until 1966.[87]

Due to the lyrics controversy and supported by the band's heavy touring schedule, the single continued to sell throughout 1965 and briefly reappeared on the charts in 1966, reaching No. 65 in Cashbox, No. 76 in Record World, and No. 97 in Billboard.[88][89] Total sales estimates for the single range from 10 million[25] to over 12 million with cover versions accounting for another 300 million.[90]

Another factor in the success of the record may have been the rumor that the lyrics were intentionally slurred by the Kingsmen—to cover up lyrics that were allegedly laced with profanity, graphically depicting sex between the sailor and his lady. Crumpled pieces of paper professing to be "the real lyrics" to "Louie Louie" circulated among teens. The song was banned on many radio stations and in many places in the United States, including Indiana, where a ban was requested by Governor Matthew Welsh.[91][92][93][94] These actions were taken despite the small matter that practically no one could distinguish the actual lyrics. Denials of chicanery by Kingsmen and Ely did not stop the controversy. The FBI started a 31-month investigation into the matter and concluded they were "unable to interpret any of the wording in the record."[17] However, drummer Lynn Easton later admitted that he yelled "Fuck" after fumbling a drum fill at 0:54 on the record.[95][96][97][98]

By the time the Kingsmen version had achieved national popularity, the band had split. Two rival editions—one featuring lead singer Jack Ely, the other with Lynn Easton who held the rights to the band's name—were competing for live audiences across the country. A settlement was reached later in 1964 giving Easton the right to the Kingsmen name but requiring all future pressings of the original version of "Louie Louie" to display "Lead vocal by Jack Ely" on the label.[99] Ely released "Love That Louie" (as Jack E. Lee and the Squires) in 1964 and "Louie Louie '66" and "Louie Go Home" (as Jack Ely and the Courtmen) in 1966 without chart success. He re-recorded "Louie Louie" in 1976 and again in 1980, and these versions appear on multiple 60s hit compilations credited to "Jack Ely (formerly of the Kingsmen)" or "re-recordings by the original artists".

Subsequent Kingsmen "Louie Louie" versions with either Lynn Easton or Dick Peterson as lead vocalist appeared on Live & Unreleased (recorded 1963, released 1992), Live at the Castle (recorded 1964, released 2011), Shindig! Presents Frat Party (VHS, recorded 1965, released 1991), 60s Dance Party (1982), California Cooler Presents Cooler Hits (recorded 1986, released 1987),[100] The Louie Louie Collection (as the Mystery Band, 1994), Red, White & Rock (2002), Garage Sale (recorded 2002, released 2003), and My Music: '60s Pop, Rock & Soul (DVD, 2011).[101]

On 9 November 1998, after a protracted lawsuit that lasted five years and cost $1.3 million, the Kingsmen were awarded ownership of all their recordings released on Wand Records from Gusto Records, including "Louie Louie". They had not been paid royalties on the songs since the 1960s.[102][103]

When Jack Ely died on April 28, 2015, his son reported that "my father would say, 'We were initially just going to record the song as an instrumental, and at the last minute I decided I'd sing it.'"[104] When it came time to do that, however, Ely discovered the sound engineer had raised the studio's only microphone several feet above his head. Then he placed Ely in the middle of his fellow musicians, all in an effort to create a better "live feel" for the recording. The result, Ely would say over the years, was that he had to stand on his toes, lean his head back and shout as loudly as he could just to be heard over the drums and guitars.[105]

When Mike Mitchell died on April 16, 2021, he was the only remaining member of the Kingsmen's original lineup who still performed with the band.[106] His "Louie Louie" guitar break has been called "iconic",[107] "blistering",[108] and "one of the most famous guitar solos of all time".[109] Guitar Player magazine noted, "Raw, lightning-fast, and loud, the solo's unbridled energy helped make the song a No. 2 pop hit, but also helped set the template for garage-rock – and later hard-rock – guitar."[110]

Paul Revere & the Raiders (1963)

| "Louie Louie" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Paul Revere & the Raiders | ||||

| from the album Here They Come! | ||||

| B-side | "Night Train" | |||

| Released | May 1963 (Sandē) June 1963 (Columbia) | |||

| Recorded | April 1963 | |||

| Length | 2:38 | |||

| Label | Sandē | |||

| Producer(s) | Roger Hart | |||

| Paul Revere & the Raiders singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Paul Revere & the Raiders also recorded a version of "Louie Louie", probably on April 11 or 13, 1963, in the same Portland studio as the Kingsmen.[111][112][113][114] The recording was paid for and produced by KISN radio personality Roger Hart, who soon became personal manager for the band. Released on Hart's Sandē label and plugged on his radio show,[111] their version was more successful locally. Columbia Records issued the single nationally in June 1963 and it went to No. 1 in the West and Hawaii, but only reached No. 103 on the Billboard Bubbling Under Hot 100 chart. The quick success of "Louie Louie" faltered, however, possibly due to lack of support from Columbia and its A&R man Mitch Miller, a former bandleader (Sing Along With Mitch) with "retrogressive taste"[115] who disliked the "musical illiteracy" of rock and roll.[116]

The Raiders version opened with a distinctive "Grab yo woman, its-a 'Louie Louie' time!" followed by a sax intro similar to the Rockin' Robin Roberts version (guitar in later releases).[117] Another distinctive lyric was "Stomp and shout and work it on out". The original version also contains a scarcely audible "dirty lyric" when Mark Lindsay says, "Do she fuck? That psyches me up!" behind the guitar solo.[118]

Robert Lindahl, president and chief engineer of NWI and sound engineer on both the Kingsmen and Raiders recordings, stated that the Raiders version was not known for "garbled lyrics" or an amateurish recording technique, but, as one author noted, their "more competent but uptight take on the song" was less exciting than the Kingsmen's version.[119]

Live versions were included on Here They Come! (1965), Paul Revere Rides Again! (1983), and The Last Madman of Rock and Roll (1986, DVD). Later releases featured different lead vocalists on Special Edition (1982, Michael Bradley), Generic Rock & Roll (1993, Carlo Driggs), Flower Power (2011, Darren Dowler), and The Revolutionary Hits of Paul Revere & the Raiders (2019, David Huizenga).

The Beach Boys (1964)

Surf music icons the Beach Boys released their version on the 1964 album Shut Down Volume 2 with lead vocals shared by Carl Wilson and Mike Love. Their effort was unusual in that it was rendered "in a version so faithful to Berry's Angeleno-revered original"[120] instead of the more common garage rock style as they "pay tribute to the two most important earlier recordings of 'Louie Louie' — the 1957 original by Richard Berry and the Pharaohs, and the infamously unintelligible 1963 cover by the Kingsmen".[121] Other surf music versions included the Chan-Dells in 1963, the Pyramids and the Surfaris in 1964, the Trashmen, the Invictas, and Jan and Dean in 1965, the Challengers in 1966, the Ripp Tides in 1981, and the Shockwaves in 1988.[122]

Otis Redding (1964)

Otis Redding's version was released on his 1964 album Pain in My Heart. Dave Marsh called it "the best of the era" and noted that he "rearranged it to suit his style" by adding a full horn section and "garbles the lyrics so completely that it seems likely he made up the verses on the spot" as he "sang a story that made sense in his life" (including making Louie a female).[123] Other versions by R&B artists included Ike & Tina Turner, the Tams, and Nat & John in 1968, Wilbert Harrison in 1969, the Topics in 1970, and Barry White in 1981.[122]

The Angels (1964)

With a version on their 1964 album A Halo to You, the Angels were the first girl group to cover "Louie Louie".[120] Their rendition also appeared on The Best of Louie Louie, Volume 2.[124]

A Minnesota girl group, the Shaggs, released a version as a 1965 single (Concert 1-78-65), and Honey Ltd. covered the song on their eponymous 1968 album and as a single (LHI 1216); however, the distinction of first girl group participation on a released version of "Louie Louie" would go to the Shalimars, an Olympia girl group who provided overdubbed backing vocals in 1960 for a recording by Little Bill (Englehardt) released as a single in 1961 (Topaz 1305).[52]

Female solo artist versions in the 1960s included Maddalena in 1967, titled "Lui Lui", as a single (RCA Italiana 3413), Tina Turner in 1968, released in 1989 on The Best of Louie Louie, Volume 2, and "a sexiest-of-all version by smokey-voiced diva Julie London"[125] released as a single (Liberty 56085) and included on her 1969 album Yummy, Yummy, Yummy.[122]

The Kinks (1964)

| "Louie Louie" | |

|---|---|

| Song by the Kinks | |

| from the EP Kinksize Session | |

| Released | November 27, 1964 |

| Recorded | October 18, 1964 |

| Studio | Pye Studios, London |

| Genre | Rhythm and blues |

| Length | 2:57 |

| Label | Pye |

| Producer(s) | Shel Talmy |

The Kinks recorded "Louie Louie" on October 18, 1964. It was released in November on the Kinksize Session EP and on two 1965 US-only albums, Kinks-Size and Kinkdom. Live 1960s versions were released on bootlegs The Kinks in Germany (1965), Kinky Paris (1965), Live in San Francisco (1969), Kriminal Kinks (1972), and The Kinks at the BBC (2012). The Kast Off Kinks continue to perform it live, occasionally joined by Ray Davies at the annual Kinks Konvention.[126]

Sources vary on the impact of "Louie Louie" on the writing of "You Really Got Me" and "All Day and All of the Night". One writer called the two songs "sparse representations of a "Louie Louie" mentality",[127] Another noted that the "You Really Got Me" riff is "unquestionably a guitar-based piece, [that] fundamentally differs from "Louie Louie" and other earlier riff pieces with which it sometimes is compared",[128] while another succinctly calls it "a rewrite of the Kingsmen's 'Louie Louie'".[129] A 1965 letter to London's Record Mirror opined, "Besides completely copying the Kingsmen's vocal and instrumental style, The Kinks rose to fame with two watery twists of this classic...."[130]

Dave Marsh asserted that the Kinks "blatantly based their best early hits" on the "Louie Louie" riff.[131] Other sources stated that Davies wrote "You Really Got Me" while trying to work out the chords of "Louie Louie" at the suggestion of the group's manager, Larry Page.[132] According to biographer Thomas M. Kitts, Davies confirmed that Page suggested that "he write a song like 'Louie Louie'", but denied any direct influence.[133]

Biographer Johnny Rogan noted no "Louie Louie" influence, writing that Davies adapted an earlier piano riff to the jazz blues style of Mose Allison, and that he was further influenced by seeing Chuck Berry and Gerry Mulligan in "Jazz on a Summer's Day", a 1958 film about the Newport Jazz Festival. Rogan also cited brother Dave Davies' distorted power chords as "the sonic contribution that transformed the composition" into a hit song.[134]

Whether directly or indirectly, the Kingsmen version influenced the musical style of the early Kinks. They were huge fans of the Kingsmen’s "Louie Louie" and Dave Davies remembered the song inspiring Ray’s singing, saying in an interview:[135][136]

We played that record over and over. And Ray copied a lot of his vocal style from that guy [Jack Ely]. I was always trying to get Ray to sing, because I thought he had a great voice, but he was very shy. Then we heard The Kingsmen and he had that lazy, throwaway, laid-back drawl in his voice, and it was magic.

The Sandpipers (1966)

After their No. 1 hit "Guantanamera", the Sandpipers, with producer Tommy LiPuma and arranger Nick DeCaro, "cleverly revived" the same soft rock, smooth ballad Spanish language approach to "Louie Louie",[137] reaching No. 30 and No. 35 on the Billboard and Cash Box charts, respectively (the highest charting U.S. version after the Kingsmen). The success of their "smoky version"[138] heralded the entry of the ever adaptable "Louie Louie" into the MOR and easy listening categories and many followed: David McCallum and J.J. Jones (1967), Honey Ltd. (1968), Julie London (1969), Sounds Orchestral (1970), Line Renaud (1973), Dave Stewart and Barbara Gaskin (1991), and others released singles and albums featuring slower and mellower versions of what had previously been an up tempo pop and rock standard.[139]

Travis Wammack (1966)

With the only instrumental version to make the charts, Travis Wammack reached No. 128 on the Bubbling Under Hot 100 in April 1966.[140] An early guitar innovator, his proto-fuzztone sound on "Louie Louie" was created by playing through an overdriven drive-in movie speaker.[141]

Released as a single (Atlantic 2322), the track was not included on Wammack's first album in 1972 or any thereafter. It appeared on a 1967 French release (Formidable Rhythm And Blues (Vol. 3)), but not again until two Wammack compilations, That Scratchy Guitar From Memphis (1987) and Scr-Scr-Scratchy! (1989). It was also included on two later various artists compilations, Love That Louie: The Louie Louie Files (2002) and Boom Boom A Go-Go! (2014).

Other notable 1960s instrumental versions included the Ventures and Ian Whitcomb in 1965, Ace Cannon and Sandy Nelson in 1966, Floyd Cramer and Pete Fountain in 1967, and Willie Mitchell in 1969.[122]

The Sonics (1966)

The Sonics released their version as a 1965 single (Etiquette ET-23) and on the 1966 album Boom. Later versions appeared on Sinderella (1980) and Live at Easy Street (2016).

Described as a major influence on punk and garage music worldwide,[142] the group's characteristic hard-edged, fuzz-drenched sound and "abrasive, all-out approach"[143] "took the Northwest garage sound to its most primitive extreme"[144] and made their "Louie Louie" version ahead of its time. They also made it more "fierce and threatening"[145] by altering the traditional 1-4-5-4 chord pattern to the "sinister-sounding" 1-3b-4-3b.[146]

Mongo Santamaria (1967)

The "Watermelon Man", Cuban percussionist and bandleader Mongo Santamaria, returned "Louie Louie" to its Afro-Cuban roots, echoing Rene Touzet's "El Loco Cha Cha" with his conga- and trumpet-driven Latin jazz version. Originally released on the 1967 album Hey! Let's Party, it was also included on the 1983 compilation The Best of Louie Louie, Volume 2.[124] Other early Latin-flavored versions were released by Pedrito Ramirez con los Yogis (Angelo 518, 1965), Pete Terrace (El Nuevo Pete Terrace, 1966), Eddie Cano (Brought Back Live from P.J.'s, 1967), Mario Allison (De Fiesta, 1967), and Rey Davila (On His Own, 1971).

Latin American jazz/rock innovator Carlos Santana compared Tito Puente's 1962 "Oye Como Va" to "Louie Louie" saying, "... how close the feel was to 'Louie Louie' and some Latin jazz tunes" [147] and "... this is a song like 'Louie Louie' or 'Guantanamera'. This is a song that when you play it, people are going to get up and dance, and that's it."[148]

Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention (1967)

"Louie Louie" repeatedly figured in the musical lexicon of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention in the 1960s; he categorized the riff as one of several "Archetypal American Musical Icons ... [whose] presence in an arrangement puts a spin on any lyric in their vicinity"[149] and used it initially "to make fun of the old-fashioned rock 'n' roll they had transcended".[7]

His original compositions "Plastic People" and "Ruthie-Ruthie" (from You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 1) were set to the melody of "Louie Louie" and included Richard Berry co-writer credits.[150] Zappa said that he fired guitarist Alice Stuart from the Mothers of Invention because she couldn't play "Louie Louie", although this comment was obviously intended as a joke.[151]

At a 1967 concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London, Mothers of Invention keyboardist Don Preston climbed up to the venue's famous pipe organ, usually used for classical works, and played the signature riff (included on the 1969 album Uncle Meat). Quick interpolations of "Louie Louie" also frequently turn up in other Zappa works.[152]

Other 1960s versions

- Little Bill with the Adventurers and the Shalimars, as a 1961 single (Topaz T-1305).[153]

- The Wailers, on their 1963 album The Wailers and Company.[122]

- The Standells, on a 1964 album The Standells in Person at P.J.s.[122]

- Pat Metheny, in the 1960s with his first group, The Beat Bombs.[154]

- John Fogerty, live in 1964 with the Golliwogs[155]

- The Bobby Fuller Four, recorded 1964, released on a French bootleg LP I Fought The Law in 1983 and on El Paso Rock: Early Recordings, Vol. 1 in 1996.[122]

- Jan and Dean, live on their 1965 Command Performance album backed by the Fantastic Baggys.[122][156]

- The Invictas, on their 1965 album The Invictas À Go-Go; re-released in 1983.[122]

- The Pink Finks (Australia), as a 1965 single (Mojo MO-001).[157]

- The Castaways, live in 1965 at the Cow Palace.[158]

- The Troggs, on their 1966 From Nowhere album. Their 1966 hit single "Wild Thing" also used a very similar chord progression. A rerecorded version was released on the 2013 album This Is The Troggs.[122][159]

- The song underwent psychedelic treatment courtesy of the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band in 1966 on their debut album Volume One, Friar Tuck on his 1967 album Friar Tuck and His Psychedelic Guitar, Neighb'rhood Childr'n on their 1997 album (recorded 1967) Long Years in Space, and the Underground All-Stars on their 1968 album Extremely Heavy!.[122]

- The Beau Brummels, on a 1966 album Beau Brummels '66 and a second version on the 1968 compilation The Best of the Beau Brummels, Vol. 44.[122]

- The Swingin' Medallions, on their 1966 album Double Shot.[122]

- The Syndicate of Sound, a live version from 1966 was released in 1991 by Cream Puff War magazine.[160]

- Jim Morrison's first vocal performance on stage was "Louie Louie" in 1965 with Rick and the Ravens (with Ray Manzarek) at the Turkey Joint West in Santa Monica.[161][162]

- Pink Floyd, in an earlier incarnation as The Pink Floyd Sound, regularly included psychedelic "Louie Louie" versions with "wild improvised interludes"[163] and "echo-laced discordant jams"[164] in their setlists in the mid-60s.[165][166]

- Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead (Joey Covington (vocals), Jerry Garcia, Jorma Kaukonen, Gary Duncan, Jack Casady, Mike Shrieve, others), live at the Family Dog at Great Highway, San Francisco on September 7, 1969.[167][168]

- The Beatles, from the Get Back/Let It Be sessions in 1969; released on the 1995 Jamming With Heather bootleg CD.[169]

1970s

Iggy Pop (1972)

Iggy Pop (then known as Jim Osterberg) began performing "Louie Louie" "with his own version of the dirty lyrics" in 1965 as a member of the Iguanas.[170] Later with the Stooges and as a solo performer, he recorded multiple versions of the song. As the "godfather of punk", he inspired a host of punk rock successors, including many with their own versions as the song became a "live staple for many punk-rock bands of the 1970s".[171][172]

An early London rehearsal version from 1972 was released on Heavy Liquid (2005) and again on Born In A Trailer (2016). A 1973 live version was released on The Detroit Tapes (2009). Metallic KO (1976) featured a provocative version with impromptu obscene lyrics from the last performance of Iggy and the Stooges in 1974 at the Michigan Palace in Detroit where, according to Lester Bangs, "you can actually hear hurled beer bottles breaking on guitar strings".[173] ("55 Minute Louie-Louie", released in 2017 by Shave on their High Alert digital album, commemorated the occasion.) Consequence called this version "a rock standard blown up from the inside out" and said, "The band’s cover of 'Louie Louie' somehow both honors their rock ‘n’ roll forebears and spits on their legacy. In other words, it's punk at its best."[174]

Pop later wrote a new version with political and satirical verses instead of obscenities that was released on American Caesar in 1993. One lyric in particular captured Pop's long term relationship with the song: "I think about the meaning of my life again, and I have to sing "Louie Louie" again."[175] Far Out Magazine called it "the best version of the song out there".[176] It was used during the opening credits of Michael Moore's Capitalism: A Love Story and as an ending song in Jim Jarmusch's Coffee and Cigarettes in which Pop took part as himself. The Just Dance video game also featured this version performed by a dancing Iggy Pop avatar.[177]

Multiple live versions were released on Nuggets (recorded 1980, released 1999), Where The Faces Shine - Volume 2 (recorded 1982, released 2008), The Legendary Breaking Point Tour (recorded 1983, released 1993), Kiss My Blood (1991, VHS), Beside You (1993), and Roadkill Rising (1994).

Toots and the Maytals (1972)

"Louie Louie" journeyed to its lyrical Jamaican destination with a reggae version by Toots and the Maytals. It was released as a 1972 UK single (Trojan TR-7865) and on the 1973 Funky Kingston album, described by rock critic Lester Bangs writing in Stereo Review as "Perfection, the most exciting and diversified set of reggae tunes by a single artist yet released".[178]

A BBC reviewer said, "The goofy garage anthem becomes both fiery sermon and dance-til-you-drop marathon. And, thanks to Toots’ soulman’s disregard for verbal meaning, the words are, if anything, even harder to discern than in the Kingsmen's version."[179] Rolling Stone wrote, "And it passes the toughest test of any 'Louie Louie' remake — it rocks hard"[180] and Hi-Fi News & Record Review cited its "imcomprehensible majesty" and "crazy vigour" that made it "the best version ever".[181] Another author, writing about the song's use in a scene in This Is England noted, "A black Jamaican band's cover of a black American song, made famous by a white American band, seems an appropriate signifier of the racial harmony that [director Shane] Meadows seeks to evoke ...."[182]

The group performed the song frequently in concert and a live version appeared on the 1998 various artists album Reggae Live Sessions Volume 2. Toots Hibbert also performed it solo and with other acts, most notably the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Dave Matthews Band.[183]

"Brother Louie" (1973)

Although musically not a true cover version, "Brother Louie", Errol Brown and Tony Wilson's song about an interracial romance, was termed by Dave Marsh as "one of the truest heirs Richard Berry's 'Louie Louie' ever had" based on its theme of separated lovers and its minor key reprise of the chorus.[184] The original release by Hot Chocolate reached No. 7 on the UK singles chart. A cover version by Stories was a No. 1 hit in the U.S. later the same year, but with the racial roles reversed.[184] In 1993, the Quireboys' version reached No. 31 in the UK.

Patti Smith (1975)

Multiple live versions by Patti Smith, the "punk poet laureate",[185] were released in the mid-1970s on bootleg albums Let's Deodorize The Night, Teenage Perversity & Ships In The Night, In Heat, and Bicentenary Blues, usually as a medley in which Lou Reed's "Pale Blue Eyes" would "sacrilegiously segue" into "Louie Louie".[122][186][187] Her cover version has been described as tapping "directly into the primal, urchin-like spirit of rock's renaissance".[188]

Jon the Postman (1977)

Described as "a committed and omnipresent figure on the punk and post-punk scene in Manchester",[189] Jon the Postman became known for waiting until headline bands like the Buzzcocks, the Fall, and Warsaw (later Joy Division)[190] had finished their sets (sometimes before they had finished) before mounting the stage in a drunken state, grabbing the microphone, and performing his own versions of "Louie Louie".[191][192] The first occurrence was at a Buzzcocks concert at the Band on the Wall venue on May 2, 1977,[193] which he described:

I think the Buzzcocks left the stage and the microphone was there and a little voice must have been calling, 'This is your moment, Jon.' I've no idea to this day why I sang 'Louie Louie,' the ultimate garage anthem from the 60s. And why I did it a cappella and changed all the lyrics apart from the actual chorus, I have no idea. I suppose it was my bid for immortality, one of those great bolts of inspiration.[194] For some reason it appeared to go down rather well. I suppose it was taking the punk ethos to the extreme – anyone can have a go. Before punk it was like you had to have a double degree in music. It was a liberation for someone like me who was totally unmusical but wanted to have a go.[195]

A version of the song by The Fall with Jon on vocals appeared on the Live 1977 album which was described by Stewart Home as taking "the amateurism of the Kingsmen to its logical conclusion with grossly incompetent musicianship and a drummer who seems to be experiencing extreme difficulty simply keeping time".[192]

A version with his group Puerile was included on the 1978 album John the Postman's Puerile.

Motörhead (1978)

| "Louie Louie" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Motörhead | ||||

| from the album Overkill (re-issue) | ||||

| B-side | "Tear Ya Down" | |||

| Released | 25 August 1978 (UK) [196] | |||

| Recorded | 1978 | |||

| Studio | Wessex, London | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 2:47 | |||

| Label | Bronze/EMI | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Motörhead singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Louie Louie" was Motörhead's first single for Bronze Records in 1978, following their initial release on Chiswick Records in 1977. A "rough-edged cover of the garage rock warhorse"[197] with Clarke's guitar emulating the Hohner Pianet electric piano riff, it was released with "Tear Ya Down" as a 7" vinyl single. Supported by a "back-breaking" touring schedule, the "high-octane" version reached No. 68 on the UK Singles Chart.[198]

The song also appeared on the CD re-issues of Overkill (1996) and The Best of Motörhead (2000). On 25 October 1978 a pre-recording of the band playing the song was broadcast on the BBC show Top of the Pops,[199] and was subsequently released on the 2005 album BBC Live & In-Session. Another live 1978 version was released on Lock Up Your Daughters (1990) and a 1978 alternate studio track appeared Over the Top: The Rarities (2000). The 2005 "deluxe edition" of Overkill included the original version, the BBC version, and two alternate versions.

National Lampoon's Animal House (1978)

Bluto Blutarsky (John Belushi) performing "Louie Louie" in National Lampoon's Animal House forever cemented the song's status as a "frat rock" classic and a staple of toga parties. Belushi may have insisted on singing "Louie Louie" because he associated it with losing his virginity, but, according to director John Landis, it was included in the screenplay by soundtrack producer Kenny Vance long before Belushi was involved with the project because "... it would be the song the Deltas would sing".[200]

In the film, the Deltas were clearly aping the Kingsmen version complete with slurred dirty lyrics, but the setting was 1962, a year before the Kingsmen recording. Although Richard Berry released his original version of the song in 1957, and the song had been popular with local bands in the Northwest following Rockin' Robin Roberts' 1961 single, the mythical Faber College was based on Dartmouth College in the Northeast U.S., so the use of "Louie Louie" was an anachronism.[200]

The Kingsmen version was heard during the film along with a brief live rendition by Belushi with Tim Matheson, Peter Riegert, Tom Hulce, Stephen Furst, Bruce McGill, and James Widdoes. A separate version by Belushi played during the credits and was included on the soundtrack album. The Belushi version was also released as a single (MCA 3046) and reached No. 89 and No. 91 on the Billboard and Cash Box charts, respectively.

Another actor from the film, DeWayne Jessie as Otis Day of Otis Day and the Knights, included a version on the VHS release Otis My Man in 1987. The film's soundtrack producer Kenny Vance (formerly of Jay and the Americans) also released a version with his group The Planotones on the 2007 album Dancin' And Romancin'.

Bruce Springsteen (1978)

Bruce Springsteen has had a long association with "Louie Louie", playing it at multiple concerts and guest appearances, and commenting often on its significance.

From the 1979 No Nukes concert:[201]

Rock is primarily about longing. All the great rock songs are about longing. "Like A Rolling Stone" is about longing; 'How does it feel to be without a home?' — "Louie, Louie"! You're yearning for –'Where's that big party that I know is out there, but I can't find it'.

From the 2018 soundtrack album for Springsteen on Broadway (spoken intro to "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out"):[202]

There is no love without one plus one equaling three. It's the essential equation of art. It's the essential equation of rock 'n' roll. It's the reason the universe will never be fully comprehensible. It's the reason "Louie Louie" will never be fully comprehensible. And it's the reason true rock 'n' roll, and true rock 'n' roll bands, will never die.

He has said that "Born in the U.S.A." was "the most misunderstood song since 'Louie Louie'",[203] and one critic characterized The River as "Less Kierkegaard, lots more Kingsmen".[204]

The first known recorded performance was on September 9, 1978 at the University of Notre Dame on the Darkness Tour, followed by other tour performances in 1978, 1981, 2009, and 2014. He also played the song in guest appearances with other groups in 1982 (at the Stone Pony with Cats on a Hot Surface) and 1983 (at The Headliner in Neptune, NJ with Midnight Thunder). Song "snippets" are frequently played within other songs: "High School Confidential", "Twist and Shout", "Glory Days", and "Pay Me My Money Down".[205]

Multiple concert bootleg albums included a live "Louie Louie" version: Reggae 'N' Soul (1988), Notre Dame Game (1981), Rockin' Days (1983), Rock Through The Jungle (1983), Rock & Roll is Here to Stay (1990), Clubs' Stories (1994), Songs for an Electric Mule (1994), Lost & Live (1995), The Boss Hits the Sixties (2009), Satisfaction (2014), Charlotte, NC 04/19/14 (2014), Who´s Been Covered By The Boss (2014), Saginaw 1978 (2015), and High Hopes Tour 2014 (2018).

E Street Band drummer Max Weinberg played "Louie Louie" on his 2017 live Jukebox show,[206] and guitarist Nils Lofgren credited some of his success to "I just happened to play 'Louie Louie' a little different than the other guys."[207] Steven Van Zandt remembered it as the record that changed his life saying, "That's where it all started."[208]

More recently, Springsteen included the Kingsmen's version in a curated "frat rock" playlist on the 25th episode of his From My Home to Yours Sirius XM radio show in July 2021.[209]

Other 1970s versions

- Allman Brothers Band, live at the 1970 Tulane University homecoming dance.[210]

- "John Lennon and Friends", at his 31st birthday party in 1971; released on the 1989 bootleg CD Let's Have A Party.[211]

- MC5, live in Helsinki in 1972; released on the Kick Copenhagen bootleg LP.[122]

- New York Dolls, live in the early 1970s;[212] their song "Private World" has been termed a "Louie Louie" update.[213]

- Flamin' Groovies, on their 1971 album Teenage Head and included on their 1976 compilation Still Shakin'. Live versions appeared on Bucketful of Brains (1983), Slow Death Live (France, 1983) and Studio '70 (France, 1984).[122]

- The Clash, on the 1977 Louie is a Punkrocker vinyl bootleg.[214][215]

- The Dictators, live at Popeye's Spinach Factory in 1977.[216]

- The Fall, on the Live 1977 album.[217]

- Spider Stacy and the New Bastards (later with The Pogues), live at Whitefields School in 1977.[218]

- The Studs, "punk-spoof supergroup" (Cabaret Voltaire members Stephen Mallinder, Richard H. Kirk, and Chris Watson, plus Ian Craig Marsh, Adi Newton, Glenn Gregory, Martyn Ware, and Haydn Boyes-Weston), live in Sheffield, UK in June 1977.[219]

- Lou Reed, live at the Bottom Line May 21, 1978.[220]

- Uh? (Julian Cope, Ian McCulloch, Dave Pickett, Pete Griffiths), live in Liverpool in 1978.[221]

- Blondie, live on the on the European Tour (December 1979-January 1980); released on the Wet Lips, Shapely Hips bootleg album.[122][222]

1980s

Black Flag (1981)

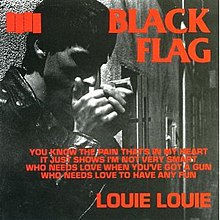

| "Louie Louie" | |

|---|---|

The cover features Black Flag's singer Dez Cadena and some of his improvised lyrics to "Louie Louie". | |

| Single by Black Flag | |

| B-side | "Damaged I" |

| Released | 1981

|

| Genre | Hardcore punk |

| Length | 5:22 |

| Label | Posh Boy |

| Producer(s) |

|

The Hermosa Beach, California, hardcore punk band Black Flag released a "raw",[223] "rubbished"[224] version of "Louie Louie" as a single in 1981 through Posh Boy Records.[225] It was the band's first release with Dez Cadena as singer, replacing Ron Reyes who had left the group the previous year.[226][227] Cadena would go on to sing on the Six Pack EP before switching to rhythm guitar and being replaced on vocals by Henry Rollins.[226][228] Cadena improvised his own lyrics to "Louie Louie", such as "You know the pain that's in my heart / It just shows I'm not very smart / Who needs love when you've got a gun? / Who needs love to have any fun?"[225] The single also included an early version of "Damaged I", which would be re-recorded with Rollins for the band's debut album, Damaged, later that year.[225] Demo versions of both tracks, recorded with Cadena, were included on the 1982 compilation album Everything Went Black.[229]

The front cover art shows the main verse of the lyrics to "Louie Louie" over a photograph by Edward Colver featuring Black Flag's third singer Dez Cadena.

Bryan Carroll of AllMusic gave the single four out of five stars, saying, "Of the more than 1,500 commitments of Richard Berry's 'Louie Louie' to wax ... Black Flag's volatile take on the song is incomparable. No strangers to controversy themselves, the band pummel the song with their trademark pre-Henry Rollins era guitar sludge, while singer Dez Cadena spits out his nihilistic rewording of the most misunderstood lyrics in rock history."[225] Both tracks from the single were included on the 1983 compilation album The First Four Years, and "Louie Louie" was also included on 1987's Wasted...Again.[230][231] A live version of "Louie Louie", recorded by the band's 1985 lineup, was released on the live album Who's Got the 10½?, with Rollins improvising his own lyrics.[232]

Continued touring, line-up changes, and occasional reunions have resulted in multiple recorded live versions with various lead singers Keith Morris, Dez Cadena, Henry Rollins, Ron Reyes, and Mike Vallely.

Stanley Clarke and George Duke (1981)

A duo of "jazz rock fusioneers",[233] bassist Stanley Clarke and keyboardist George Duke, included a "killer version"[234] "funk cover"[235] on The Clarke/Duke Project, a 1981 album of eight original compositions and one cover. The song's combination of narration and singing within a storytelling structure elicited a variety of critic's reactions ranging from "appealing"[236] and "imaginative adaptation[233] to "probably the funkiest version of 'Louie Louie' ever recorded".[237] One Allmusic reviewer called it "a truly bizarre rendition"[238] while another lamented that the Clarke/Duke version "criminally, never made it onto any of the various artists collections that showcased the legendary Richard Berry tune."[235]

A single was also released in Europe (cut to 3:38 from the album's 5:05 length).[239] The album was nominated for a 1982 Grammy Award for Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals.

The Fat Boys (1988)

The Fat Boys with producers Latin Rascals brought "Louie Louie" up to date in 1988 with a hip hop version which reached No. 89 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and No. 46 on the UK Top 100. Their rap, with rewritten lyrics, "chronicled a pursuit of the song's real words".[240]

The Fat Boys version was released on the Coming Back Hard Again album on the Tin Pan Apple label, and also on a 12" single (5:42 and 3:50 edits) and a 7" single (3:50 edit). The 2009 compilation album Fat Boys On Rewind included it as well.[241] Notable live performances in 1988 included Club MTV and the MTV Video Music Awards.

The music video, directed by Scott Kalvert, was a parody of Animal House with food fights, dancing girls, and togas. Dave Marsh in 1993 called their version "the last great "Louie Louie" to date".[240]

The year 1988 also saw multiple rap and hip hop releases with "Louie Louie" sampling (see Use in sampling section below).

Other 1980s versions

- Barry White, on his 1981 album Beware.[242]

- The Grateful Dead, multiple live versions in the 1980s with Brent Mydland on vocals.[243]

- Joan Jett & the Blackhearts, on the 1992 CD reissue of the 1981 album I Love Rock 'n Roll; one of multiple versions that deliberately repeated the Jack Ely early vocal entry mistake.[67][244]

- 39 Clocks (Germany), recorded as "Psychotic Louie Louie", on their 1982 album Subnarcotic.[122]

- Rory Gallagher, live at the Olympia Hall Paris in 1982; released on the 2022 album A Burning Fever.[245]

- The Last, on the 1983 various artists album The Best of Louie Louie, also released on Painting Smiles on a Dead Man (France, 1983).[122]

- Australian Crawl, on their 1983 album Phalanx and as a single; also released on the 1986 album The Final Wave as "(The Last) Louie Louie".[122]

- The Bangles, in 1984 on MTV's The Cutting Edge.[246]

- The Kingsmen, in an audience performance at the end of Bud Clark's Inaugural Ball beginning his term as Mayor of Portland, Oregon in 1985.[247]

- Girl Trouble, on the 1990 album Stomp And Shout And Work It On Out !!!! (recorded 1985).[122]

- The Sisters of Mercy, on the 1985 EP Brimstone & Treacle. Various live versions appeared on bootleg albums Possession, Half Moon Over Amsterdam, The Lights Shine Clear Through The Sodium Haze, A Fire In The Hull, At The Blind Parade, Cryptic Flowers, Live In Maastricht, Tune In... Turn Off... Burn Out..., and The Quality Of Mercy.[122]

- Hüsker Dü, Meat Puppets, Minutemen, Saccharine Trust, and SWA, on the 1986 VHS release The Tour.[248]

- Meat Loaf, in multiple concerts in Germany, Switzerland, and the UK on the 20/20 World Tour in 1987.[249]

- Paul Shaffer, on the 1989 album Coast to Coast.[122]

- John Stamos with Scott Baio and cast members, on Full House S3E9 (November 24, 1989).[250]

1990s

Coupe de Ville (1990)

Written by Mike Binder and directed by Joe Roth, Coupe de Ville featured an extended scene discussing possible interpretations of the "Louie Louie" lyrics and a closing credit montage of multiple "Louie Louie" versions.

Hearing the Kingsmen version on a car radio sparks an extended debate among the three Libner brothers (Patrick Dempsey, Arye Gross, Daniel Stern) about the lyrics and whether it is a "hump song", a "dance song", or a "sea chanty" with the eldest and most worldly brother arguing for the last interpretation.[251][252] As the Los Angeles Times noted, "Joe Roth obviously knows the importance of the "Louie Louie" lyric controversy".[253]

Multiple versions played during the closing credits: Richard Berry, the Rice University Marching Owl Band, the Sandpipers, Les Dantz and his Orchestra,[254] the Kingsmen, and Young MC’s "Louie Louie House Mix" (a remix of the Kingsmen version with samples from Richard Berry and the Rice University MOB). The movie trailer also used the Richard Berry and Kingsmen versions.

The soundtrack album, released by Cypress Records on vinyl, CD and cassette, included the Kingsmen and Young MC versions. A 12" EP (Cypress Records V-74500) was released with four tracks: "Louie Rap", "Louie Vocal Attack", "Louie Louie House Mix", and "Louie DePalma Mix" (all "featuring Maestro Fresh Wes" and "produced by Young MC").

A music video of "Louie Louie House Mix", credited to "Various Artists (featuring Young MC)", was concurrently released and included appearances by Robert Townsend ("It’s a hump song!"), Kareem Abdul Jabbar ("It’s a dance song!"), Martin Short, Young MC, and others.

The inclusion of the Kingsmen's "Louie Louie" is a bit of an anachronism in that the film takes place on a trip from Detroit to Florida during the summer of 1963. The initial release of the Kingsmen version on the regional Jerden label was in May 1963, but no significant national radio airplay and chart activity (or lyrics controversy) occurred until October and its national chart debut was not until early November.[255]

The Three Amigos (1999)

The first release by the Three Amigos (Dylan Amlot, Milroy Nadarajah, and Marc Williams) was their cover of "Louie Louie". The 12" EP, titled Louie Louie, included "Original Mix", "Da Digglar Mix", "Wiseguys Remix", and "Touché's Bonus Beats". Released in July 1999, the "Original Mix" version reached No. 15 on the UK Singles Chart, higher than the Kingsmen's No. 26 in 1964, and to date remains the last "Louie Louie" version to appear on the US or UK charts.[256]

The group's logo paid tribute to the logo of the Kingsmen.[257]

Other 1990s versions

- Johnny Winter, on the 1990 album A Lone Star Kind of Day.[122]

- Ry Cooder, live in 1990 at a Village Music function with Richard Berry, Tim Drummond, Scott Mathews, Steve Douglas, and Johnnie Johnson.[258]

- The Dave Matthews Band, in some of their early 1990s setlists. A version was included on the 2000 album The Best Of What's Around Vol. 1.[259]

- John Stamos and David Coulier, on Full House S7E3 (September 28, 1993) with Dylan & Blake Tuomy-Wilhoit.[260]

- The Queers, on a bonus 7" record included with the 1994 Shout at the Queers album.[261]

- Neil Diamond, live at the 1995 NYU commencement ceremony.[262]

- At the 1997 opening of the Experience Music Project, an encore version was performed by the Kingsmen joined by Paul Allen, the Presidents of the United States of America, and Steve Turner of Mudhoney. The other members of Mudhoney declined to participate.[263]

- Warren Zevon, live with the Rock Bottom Remainders in Bangor, Maine in 1998. Horror author Stephen King sang lead, and music critic Joel Selvin performed an extended "scream solo".[264]

2000s

- The Guess Who, in their 2000 reunion concert in Winnipeg.[265] Burton Cummings regularly performed live versions at various concerts.[266]

- Steve Jordan, released an innovative, "blatantly personal"[267] Tejano conjunto version on his 2005 album 25 Golden Hits.[268]

- Mike Huckabee and Capitol Offense, live at HuckPAC 2008.[269]

- Lisa Simpson and the Springfield Children's Band, on the 2005 episode of The Simpsons (Episode 367: "We’re on the Road to D’ohwhere").[270]

- Dick Dale, live at the Surf Club in Ortley Beach, NJ in 2007.[271]

- Joe McPhee, Cato Salsa Experience, and The Thing, on the 2007 album Two Bands And A Legend.[272]

- Eddie Angel and Johnny Rabb with The Trashmen, live at the Turf Club in St. Paul, MN on November 22, 2008.[273]

- The Hives, live with The Sonics November 27, 2009 at Debaser Medis, Stockholm, Sweden.[274]

- The Smashing Pumpkins, on their 2008 Live Smashing Pumpkins album series.[275]

- Detroit7 (Japan), on two 2009 albums, Detroit7 and Black & White.[276]

- James Williamson with Careless Hearts, on their eponymous 2009 album.[277]

2010s

- Baby It's You!, a 2011 Broadway jukebox musical, featured a production of "Louie Louie" by cast members as the Kingsmen, the Shirelles and Chuck Jackson that was released on the original cast soundtrack album.[278]

- Billy Joel, live at the Moda Center in Portland on December 8, 2017.[279]

2020s

- The September 2021 issue of Rolling Stone magazine published a revised list of Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time that ranked "Louie Louie" No. 156, down from No. 54 in the 2004 and 2010 rankings.[280]

Foreign language versions

Shortly after the Kingsmen's version charted in late 1963, the first international covers appeared. Since the original lyrics were notoriously difficult to discern, the translations were often inaccurate or adapted to a different storyline. Early foreign language versions included:[281]

- Los Apson (Mexico), as "Ya No Lo Hagas", on a 1963 single (Peerless 1263) and a 1964 album Atrás De La Raya

- Joske Harry's and the King Creoles (Belgium), on a 1963 single (Arsa 107)

- Les Players (France), as "Si C'Etait Elle", on a 1964 single (Polydor 1879) and a 1964 EP (Polydor 27 129)

- Los Supersónicos (El Salvador), on a 1965 single (DCA 1082) and eponymous album

- Pedrito Ramirez con Los Yogis (US), on a 1965 single (Angelo 518)

- I Trappers (Italy), as "Lui Lui Non Ha", on a 1965 single (CGD 9606)

- Los Corbs (Spain), as "Loui Loui", on a 1966 EP (Marfer M.622)

- Les Zèniths (Canada), on a 1966 single (Première 825)

- Maddalena (Italy), as "Lui Lui" on a 1967 single (RCA Italiana 3413)

- Los Yetis (Colombia), on a 1968 album Olvidate

In 1966 the Sandpipers, a US group, released a slower tempo Spanish language version that reached No. 30 on the Billboard Hot 100 and was covered that same year in German by Die Rosy-Singers.[282]

The 1983 compilation The Best of Louie, Louie featured a Russian version by Red Square,[30] and in 1997 an entire album of Spanish covers, The First Louie Louie Spanish Compilation, was released with versions by the Flaming Sideburns, the Navahodads, Los DelTonos, and eight others.[242] Other Spanish versions were released by Los Hermanos Carrion (Mexico), as "Alu, Aluai" on a 1971 album Lagrimas de Cristal Que Manera de Perder, Los Elegantes (Spain), as "Luisa Se Va" on a 1985 album Paso A Paso,[283] and Desperados (Spain), on a 1997 album Por Un Puñado De Temas.

In 1988, Michael Doucet released a "great vocal treatment"[284] of "Louie Louie" in Cajun French on the Michael Doucet and Cajun Brew album.[242] CD Review characterized his version as "oddly appropriate".[285]

More recent non-English efforts included:

- Elektricni Orgazam (Serbia), as "Lui Lui", on a 1986 album Distorzija

- Irha (Italy), as "Lui Luisa", on a 1989 EP Beati I Primi (Attack Punk Records - APR 12)[286]

- Eläkeläiset (Finland), as "Tilulilulei", on a 1994 album Joulumanteli

- The Dizzy Brains (Madagascar), as "Hiala Aho Zao", on a 2014 album Môla Kely

- Dynasis (Greece), as "Loui Loui" on a 2019 digital single[287]

Answer songs, sequels, and tributes

"Louie Louie" has spawned a number of answer songs, sequels, and tributes from the 1960s to the present:[288]

- "Louie Go Home", 1964, Paul Revere & the Raiders (Columbia 4-43008); also released in 1964 by Davie Jones & The King Bees (David Bowie) as "Louie Louie Go Home" (Vocalion V9221).

- "Love That Louie", 1964, Jack E. Lee & The Squires (RCA 54-8452)

- "Louie Come Home", 1965, The Epics (Zen 202)

- "Louie Come Back", 1965, The Legends (Shout! Northwest Killers Volume 2, Norton NW 907)

- "Louise Louise", 1966, H.B. & The Checkmates (Lavender R1936)

- "Louie Go Home", 1966, The Campus Kingsmen (Impalla V 1481); different song from the Raiders version

- "Louie Louie's Comin' Back", 1967, The Pantels (Rich RR-120)

- "Louie Louie Louie", 1989, Henry Lee Summer (I've Got Everything, CBS ZK 45124)

- "Louie Louie Got Married", 1994, The Tentacles (K Records IPU XCIV)

- "Louie Louie (Where Did She Roam)", 1996, Thee Headcoats (SFTRI 335)

- "Ballad of the Kingsmen", 2004, Todd Snider (East Nashville Skyline, Oh Boy Records OBR-031)

- "Louie Louie Music", 2012, Armitage Shanks (Louie Louie Music EP, Little Teddy LiTe765)

- "I Love Louie Louie", 2014, The Rubinoos (45, Pynotic Productions 0045)

- "55 Minute Louie-Louie", 2017, Shave (High Alert, digital album)

- "I Wanna Louie Louie (All Night Long)", 2020, Charles Albright (Everything Went Charles Albright, digital album)

"Louie Louie" compilations

- In 1983 Rhino Records released The Best of Louie, Louie in conjunction with KFJC's "Maximum Louie Louie" event. The album featured a re-recorded Richard Berry version,[32] influential versions by Rockin' Robin Roberts, the Sonics and the Kingsmen, Black Flag's version, and several other versions, some bizarre. These included a performance by the Rice University Marching Owl Band, an a cappella "Hallalouie Chorus", in which the song's title was sung to the melody of Handel's "Hallelujah Chorus", and a David Bowie imitation by Les Dantz and his Orchestra.[30]

- The Best of Louie Louie, Volume 2 followed in 1992 with versions by Paul Revere and the Raiders, Mongo Santamaria, Pete Fountain, the Kinks, Ike and Tina Turner, the Shockwaves, and others.[124]

- In 1994 Jerden Records released The Louie Louie Collection, a Northwest-oriented compilation featuring versions by the Kingsmen, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Don & the Goodtimes, Little Bill & the Adventurers, the Feelies, Ian Whitcomb, the University of Washington Husky Marching Band, and others. (The UW Husky Marching Band has been playing "Louie Louie" for over 40 years.)[289]

- In 1997 The First Louie Louie Spanish Compilation was released by Louie Records featuring 11 versions by the Flaming Sideburns, the Navahodads, Los DelTonos, and others.[242]

- In 2002 Ace Records released Love That Louie: The Louie Louie Files, a comprehensive overview of the origins, impact and legacy of "the cultural phenomenon known as 'Louie Louie'." Featuring detailed sleeve notes by Alec Palao, the CD contains 24 tracks divided into eight sections titled "The Original Louie", "Inspirational Louie", "Northwest Louie", "Louie As A Way Of Life", "Transatlantic Louie", "Louie: The Rewrite", "Louie: The Sequel" and "Louie Goes Home". The first CD reissue of Richard Berry's original version is included along with multiple historically important versions.[290]

Lyrics controversy and investigations

As "Louie Louie" began to climb the national charts in late 1963, Jack Ely's "slurry snarl"[291] and "mush-mouthed",[292] "gloriously garbled"[293] vocals gave rise to dark rumors about "dirty lyrics". The Kingsmen initially ignored the rumors, but soon "news networks were filing reports from New Orleans, Florida, Michigan, and elsewhere about an American public nearly hysterical over the possible dangers of this record".[72] The song quickly became "something of a Rorschach test for dirty minds".[294]

In January 1964, Indiana governor Matthew E. Welsh, acting on multiple complaint letters, determined the lyrics to be pornographic because his "ears tingled" when he listened to the record.[295][296] He referred the matter to the FCC (which declined to act) and also requested that the Indiana Broadcasters Association advise their member stations to pull the record from their playlists. The National Association of Broadcasters also investigated and deemed it "unintelligible to the average listener", but that "The phonetic qualities of this recording are such that a listener possessing the 'phony' lyrics could imagine them to be genuine."[297] In response, Max Feirtag of publisher Limax Music offered $1,000 to "anyone finding anything suggestive in the lyrics",[298] and Broadcasting magazine published the actual lyrics as provided by Limax.[299] Scepter/Wand Records commented, "Not in anyone's wildest imagination are the lyrics as presented on the Wand recording suggestive, let alone obscene."[300]

The following month an outraged parent wrote to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy alleging that the lyrics of "Louie Louie" were obscene, saying, "The lyrics are so filthy that I can-not [sic] enclose them in this letter."[301][302] The Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated the complaint,[303] and looked into the various rumors of "real lyrics" that were circulating among teenagers.[304] In June 1965, the FBI laboratory obtained a copy of the Kingsmen recording and, after 31 months of investigation, concluded that it could not be interpreted, that it was unintelligible at any speed,[305] and therefore the Bureau could not find that the recording was obscene.[17] Over the course of the investigation, the FBI interviewed Richard Berry, members of the Kingsmen, members of Paul Revere and the Raiders, and record company executives. The one person they never interviewed was the man who actually sang the words in question, Jack Ely, whose name apparently never came up because he was no longer with the Kingsmen.[304][306][307]

By contrast, in 1964 the Ohio State University newspaper The Lantern initiated an investigation in response to a growing campus controversy. Working with local radio station WCOL, a letter was sent to Wand Records requesting a copy of the lyrics. The paper printed the lyrics in full, resolving the issue, and resulting in booking the Kingsmen for the fall homecoming entertainment.[308]

In a 1964 interview, Lynn Easton of the Kingsmen said, "We took the words from the original version and recorded them faithfully."[296] Richard Berry told Esquire Magazine in 1988 that the Kingsmen had sung the song exactly as written[21] and often deflected questions about the lyrics by saying, "If I told you the words, you wouldn't believe me anyway."[309][310]

A history of the song and its notoriety was published in 1993 by Dave Marsh, including an extensive recounting of the multiple lyrics investigations,[311] but he was unable to obtain permission to publish the song's actual lyrics[312] because the then current owner, Windswept Pacific, wanted people to "continue to fantasize what the words are".[313] Marsh noted that the lyrics controversy "reflected the country's infantile sexuality" and "ensured the song's eternal perpetuation"; he also included multiple versions of the supposed "dirty lyrics".[18] Other authors noted that the song "reap[ed] the benefits that accrue from being pursued by the guardians of public morals"[314] and "Such stupidity helped ensure 'Louie Louie' a long and prosperous life."[315]

The lyrics controversy resurfaced briefly in 2005 when the superintendent of the school system in Benton Harbor, Michigan, refused to let a marching band play the song in a local parade; she later relented.[316][317]

Cultural impact

The Who

The Who were impacted in their early recording career by the riff/rhythm of "Louie Louie", owing to the song's influence on the Kinks, who, like the Who, were produced by Shel Talmy. Talmy wanted the successful sounds of the Kinks' 1964 hits "You Really Got Me", "All Day and All of the Night", and "Till the End of the Day" to be copied by the Who.[120] As a result, Pete Townshend penned "I Can't Explain", "a desperate copy of The Kinks",[318] released in March 1965. In 1979 "Louie Louie" (Kingsmen version) was included on the soundtrack album to Quadrophenia.

"Psyché Rock" and Futurama

In 1967 French composers Michel Colombier and Pierre Henry, collaborating as Les Yper-Sound, produced a synthesizer and musique concrète work based on the "Louie Louie" riff titled "Psyché Rock".[319] They subsequently worked with choreographer Maurice Béjart on a "Psyché Rock"-based score for the ballet Messe pour le temps présent. The full score with multiple mixes of "Psyché Rock" was released the same year on the album Métamorphose. The album was reissued in 1997 with additional remixes including one by Ken Abyss titled "Psyché Rock (Metal Time Machine Mix)" that, along with the original, heavily influenced Christopher Tyng's Futurama theme song.[320][321]

Radio station marathons

In the early 1980s KALX in Berkeley and KFJC in Los Altos Hills engaged in a "Louie Louie" marathon battle with each station increasing the number of versions played. KFJC's Maximum Louie Louie Marathon topped the competition in August 1983 with 823 versions played over 63 hours, plus in studio performances by Richard Berry and Jack Ely.[322][323] During a change in format from adult-contemporary to all-oldies in 1997, WXMP in Peoria became "all Louie, all the time," playing nothing but covers of "Louie Louie" for six straight days.[324] Other stations used the same idea to introduce format changes including KROX (Dallas), WNOR (Norfolk), and WRQN (Toledo).[325] In 2011, KFJC celebrated International Louie Louie Day with a reprise of its 1983 event, featuring multiple "Louie Louie" versions, new music by Richard Berry and appearances by musicians, DJs, and celebrities with "Louie Louie" connections.[326] In April 2015 Orme Radio broadcast the First Italian Louie Louie Marathon, playing 279 versions in 24 hours.[327]

Use in movies

Various versions of "Louie Louie" have appeared in the films listed below.[328]

| Year | Title | Version(s) | On OST Album |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Zavolies (Ζαβολιές) [lower-alpha 1] | Fotis Lazaridis Orchestra | n/a | Greece release |

| 1972 | Tijuana Blue [lower-alpha 2] | Kingsmen | n/a | |

| 1973 | American Graffiti | Flash Cadillac | No [lower-alpha 3] | |

| 1978 | National Lampoon's Animal House | Kingsmen, John Belushi | Yes [lower-alpha 4] | |

| 1979 | Quadrophenia | Kingsmen | Yes [lower-alpha 5] | |

| 1983 | Heart Like A Wheel | Jack Ely | No | |

| Nightmares | Black Flag | Yes | ||

| 1984 | Blood Simple | Toots and the Maytals | No | |

| 1986 | The Cult: Live In Milan [lower-alpha 6] | The Cult | No | Italy release |

| 1987 | Survival Game [lower-alpha 7] | Kingsmen | n/a | Also in trailer |

| The Return of Sherlock Holmes | Cast (uncredited bar band) | n/a | TV movie | |

| 1988 | The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! | Marching Owl Band [lower-alpha 8] | Yes | |

| Love at Stake | Kingsmen | No | ||

| 1989 | Fright Night Part 2 | Black Flag | No | |

| 1990 | Coupe de Ville | Kingsmen, Young MC [lower-alpha 9] | Yes | |

| 1991 | Reality 86'd | Black Flag | n/a | |

| 1992 | Jennifer 8 | Kingsmen | No | |

| Passed Away | Kingsmen | Yes | ||

| Dave | Cast (Kevin Kline) | No | ||

| 1993 | Wayne's World 2 | Robert Plant | Yes[lower-alpha 10] | |

| 1994 | A Simple Twist of Fate | Cast (party singalong) | No | |

| 1995 | Mr. Holland's Opus | Cast (student band instrumental) | No | |

| Man of the House | Kingsmen | n/a | ||

| 1996 | Down Periscope | Cast (Kelsey Grammer and others) | n/a | |

| 1997 | My Best Friend's Wedding | Kingsmen | No | |

| 1998 | ABC - The Alphabetic Tribe [lower-alpha 11] | Kingsmen, Sandpipers | n/a | Swiss release |

| Wild Things | Iggy Pop | No | ||

| 2001 | Say It Isn't So | Kingsmen | No | |

| 2002 | La Bande du drugstore | Full Spirits | Yes | France release |

| 24 Hour Party People | John The Postman, Factory All Stars | No | UK release | |

| 2003 | Old School | Black Flag | Yes | |

| Coffee and Cigarettes | Richard Berry, Iggy Pop | Yes | ||

| 2004 | Friday Night Lights | Cast (marching band instrumental) | No | |

| 2005 | Guy X | Kingsmen | n/a | |

| 2006 | This Is England | Toots and the Maytals | Yes | UK release |

| Bobby | Cast (Demi Moore) [lower-alpha 12] | Yes | ||

| 2009 | Capitalism: A Love Story | Iggy Pop | n/a | |

| 2010 | Lemmy | Motörhead | n/a | UK release |

| Knight and Day | Kingsmen[lower-alpha 13] | No | ||

| Tournée | Nomads, Kingsmen | Yes [lower-alpha 14] | France release | |

| 2012 | Best Possible Taste: The Kenny Everett Story [lower-alpha 15] | Kingsmen | n/a | UK TV movie |

| 2013 | Il était une fois les Boys | King Melrose | Yes | Canada release |

| Her Aim Is True | Sonics, Wailers | n/a | Sonics version also in trailer | |

| 2014 | Desert Dancer | Jack Ely | No | UK release |

| 2018 | A Futile and Stupid Gesture | Kingsmen | n/a | |

| 2020 | The Way Back | Cast (pep band instrumental) | No | |

| 2021 | Penguin Bloom | Kingsmen | n/a | Australia release |

The Kingsmen version was used in television commercials for Spaced Invaders (1990), but did not appear in the movie.[lower-alpha 16] The Kingsmen version also appeared on More American Graffiti (1975) and Good Morning Vietnam (1987) compilations, but was not used in either movie.

- Movie table notes

- Zavolies at IMDb