music.wikisort.org - Composition

Nevermind is the second studio album by the American rock band Nirvana, released on September 24, 1991, by DGC Records. It was Nirvana's first release on a major label and the first to feature drummer Dave Grohl. Produced by Butch Vig, Nevermind features a more polished, radio-friendly sound than the band's prior work.[4] It was recorded at Sound City Studios in Van Nuys, California, and Smart Studios in Madison, Wisconsin in May and June 1991, and mastered that August at the Mastering Lab in Hollywood, California.

| Nevermind | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | September 24, 1991 | |||

| Recorded | May 2–28, 1991[1][2] June 1–9, 1991 (mixing)[3] April 1990 ("Polly") | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 42:36 (49:15 with hidden track) | |||

| Label | DGC | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Nirvana chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Nevermind | ||||

| ||||

Written primarily by frontman Kurt Cobain, the album is noted for channeling a range of emotions, being noted as dark, humorous, and disturbing. Thematically, it includes anti-establishment views, anti-sexism, frustration, alienation and troubled love inspired by Cobain's broken relationship with Bikini Kill's Tobi Vail. Contrary to the popular hedonistic themes of drugs and sex at the time, writers have observed that Nevermind re-invigorated sensitivity to mainstream rock. According to Cobain, the sound of the album was influenced by bands such as Pixies, R.E.M., the Smithereens, and the Melvins. Though the album is considered a cornerstone of the grunge genre, it is noted for its musical diversity, which includes acoustic ballads ("Polly" and "Something in the Way") and punk-inspired hard rock ("Territorial Pissings" and "Stay Away").[5]

Nevermind became an unexpected critical and commercial success, charting highly on charts across the world. By January 1992, it reached number one on the US Billboard 200 and was selling approximately 300,000 copies a week. The lead single "Smells Like Teen Spirit" reached the top 10 of the US Billboard Hot 100 and went on to be inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Its video was also heavily rotated on MTV. Three other successful singles were released: "Come as You Are", "Lithium", and "In Bloom". The album was voted the best album of the year in Pazz & Jop critics' poll, while "Smells Like Teen Spirit" also topped the single of the year and video of the year polls. The album also garnered the band three Grammy Award nominations in total across the 34th and 35th Grammy Awards, including Best Alternative Music Album.

Nevermind and its singles' success propelled Nirvana to being widely regarded as the biggest band in the world, with Cobain being dubbed by critics as the "voice of his generation.” The album brought grunge and alternative rock to a mainstream audience while ending the dominance of hair metal, drawing similarities to the early 1960s British Invasion of American popular music. It is also often credited with initiating a resurgence of interest in punk culture among teenagers and young adults of Generation X. It has sold more than 30 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling albums of all time. In March 1999, it was certified Diamond by the RIAA. Among the most acclaimed and influential albums in the history of music, it was added to the National Recording Registry in 2004 as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically important", and is frequently ranked on lists of the greatest albums of all time.

Background

In early 1990, Nirvana began planning their second album for their record company Sub Pop, tentatively titled Sheep. At the suggestion of Sub Pop head Bruce Pavitt, Nirvana selected Butch Vig as producer.[6] The band particularly liked Vig's work with Killdozer.[7] They traveled to Vig's Smart Studios in Madison, Wisconsin, and recorded from April 2 to 6, 1990.[8] Most of the basic arrangements were complete, but songwriter Kurt Cobain was still working on lyrics and the band was unsure of which songs to record.[9] Ultimately, eight were recorded, some of which appeared on Nevermind: "Imodium" (later renamed "Breed"), "Dive" (later released as the B-side to "Sliver"), "In Bloom", "Pay to Play" (later renamed "Stay Away"), "Sappy", "Lithium", "Here She Comes Now" (released on Velvet Underground Tribute Album: Heaven and Hell Volume 1), and "Polly".[10]

On April 6, Nirvana played a local show in Madison with fellow Seattle band Tad.[11] Vig began to mix the recordings while the band were in Madison, giving[clarification needed] an interview to Madison's community radio station WORT on April 7.[12] Cobain strained his voice, forcing Nirvana to end recording. On April 8, they travelled to Milwaukee to begin an extensive midwest and east coast tour of 24 shows in 39 days.[13]

Drummer Chad Channing left after the tour, putting additional recording on hold.[14] During a show by hardcore punk band Scream, Cobain and bassist Krist Novoselic were impressed by their drummer Dave Grohl. When Scream unexpectedly disbanded, Grohl contacted Novoselic, travelled to Seattle, and was invited to join the band. Novoselic said in retrospect that, with Grohl, everything "fell into place".[6]

By the 1990s, Sub Pop was having financial problems. With rumors that they would become a subsidiary of a major record label, Nirvana decided to "cut out the middleman" and look for a major record label.[6] Nirvana used the recordings as a demo tape to shop for a new label. Within a few months, the tape was circulating amongst major labels.[14] A number of labels courted them; Nirvana signed with Geffen Records imprint DGC Records based on recommendations from Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth and their management company.[15]

After Nirvana signed to DGC, a number of producers were suggested, including Scott Litt, David Briggs, Don Dixon, and Bob Mould.[16] Novoselic said the band had been nervous about recording under a major label, and the producers suggested by DGC wanted percentage points. Instead, the band held out for Vig, with whom they felt comfortable collaborating.[17]

Recording

With a budget of $65,000, Nirvana recorded Nevermind at Sound City Studios in Van Nuys, California, in May and June 1991.[18] To earn gas money to get to Los Angeles, they played a show where they performed "Smells Like Teen Spirit" for the first time.[6] The band sent Vig rehearsal tapes prior to the sessions that featured songs recorded previously at Smart Studios, plus new songs including "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and "Come as You Are".[19]

Nirvana arrived in California and spent a few days rehearsing and working on arrangements.[20] The only recording carried over from the Smart Studios sessions was "Polly", including Channing's cymbal crashes. Once recording commenced, the band worked eight to ten hours a day.[21] Cobain used a variety of guitars, from Stratocasters to Jaguars, and Novoselic used a black 1979 and natural 1976 Gibson Ripper. Novoselic and Grohl finished their tracks in days, while Cobain worked longer on guitar overdubs, vocals, and lyrics; he sometimes finished lyrics minutes before recording.[22] Vig recalled that Cobain was often reluctant to record overdubs, but was persuaded to double-track his vocals when he told him that John Lennon did it.[6] Though the sessions generally went well, Vig said Cobain would become difficult at times: "He'd be great for an hour, and then he'd sit in a corner and say nothing for an hour."[7]

Mixing and mastering

Vig and the band were unhappy with Vig's initial mixes and decided to bring in someone else to oversee the mixing. DGC supplied a list of options, including Scott Litt (known for his work with R.E.M.) and Ed Stasium (known for his work with the Ramones and the Smithereens). Cobain was concerned about bringing in well known producers, and instead chose Andy Wallace, who had co-produced Slayer's 1990 album Seasons in the Abyss.[23] Novoselic recalled, "We said, 'right on,' because those Slayer records were so heavy."[24] Wallace's mixes most notably altered the drum and guitar sounds.[25] According to Wallace and Vig, the band loved the results.[26] However, they criticized it after the album was released. Steve Albini, who engineered Nirvana's next album, In Utero (1993), said Vig's initial mix "sounded maybe 200 times more ass-kicking" than the final version of Nevermind and that Nirvana referred to it while working on In Utero.[27]

Nevermind was mastered on the afternoon of August 2 at the Mastering Lab in Hollywood, California. Howie Weinberg started working alone when no one else arrived at the appointed time in the studio; by the time Nirvana, Andy Wallace, and Gary Gersh arrived, Weinberg had mastered most of the album.[28] A hidden track, "Endless, Nameless", intended to appear at the end of "Something in the Way", was accidentally left off initial pressings of the album. Weinberg recalled, "In the beginning, it was kind of a verbal thing to put that track at the end. (...) Maybe I didn't write it down when Nirvana or the record company said to do it. So, when they pressed the first twenty thousand or so CDs, albums, and cassettes, it wasn't on there." Cobain called Weinberg and demanded he rectify the mistake.[29]

Music

At the time of writing Nevermind, Cobain was listening to bands such as the Melvins, R.E.M., the Smithereens, and Pixies, and was writing songs that were more melodic. A key development was the single "Sliver", released on Sub Pop in 1990 before Grohl joined, which Cobain said "was like a statement in a way. I had to write a pop song and release it on a single to prepare people for the next record. I wanted to write more songs like that."[30] Grohl said that the band at that point likened their music to children's music, in that they tried to make their songs as simple as possible.[6]

Cobain fashioned chord sequences using primarily power chords and wrote songs that combined pop hooks with dissonant guitar riffs. His aim for Nevermind's material was to sound like "the Knack and the Bay City Rollers getting molested by Black Flag and Black Sabbath".[31] Many songs feature shifts in dynamics, whereby the band changes from quiet verses to loud choruses. Grohl said this approach originated during a four-month period prior to the recording of the album, when the band would experiment with extreme dynamics during regular jam sessions.[32]

Guitar World wrote, "Kurt Cobain's guitar sound on Nirvana's Nevermind set the tone for Nineties rock music." On Nevermind, Cobain played a 1960s Fender Mustang, a Fender Jaguar with DiMarzio pickups, and a few Fender Stratocasters with humbucker bridge pickups. He used distortion and chorus pedals as his main effects, the latter used to generate a "watery" sound on "Come as You Are" and the pre-choruses of "Smells Like Teen Spirit".[33] Novoselic tuned down his bass guitar one and a half steps to D flat "to get this fat-ass sound".[17]

After the release of Nevermind, members of Nirvana expressed dissatisfaction with the production for its perceived commercial sound. Cobain said, "I'm embarrassed by it now. It's closer to a Mötley Crüe record than it is a punk rock record."[25] In 2011, Vig said that Nirvana had "loved" Nevermind when they finished it. He said Cobain had criticized it in the press "because you can't really go, 'Hey, I love our record and I'm glad it sold 10 million copies.' That's just not cool to do. And I think he felt like he wanted to do something more primal."[34]

Lyrics

The album is noted for channeling a range of emotions, being noted as dark, humorous, and disturbing.[35] Thematically, it includes anti-establishment views,[36] and lyrics about sexism,[37] frustration, loneliness, sickness, and troubled love.[38] Contrary to the popular hedonistic themes of drugs and sex at the time, writers have observed that the album re-invigorated sensitivity to mainstream rock.[39] Grohl has said that Cobain told him, "Music comes first and lyrics come second," and Grohl believes that above all Cobain focused on the melodies of his songs.[6] Cobain was still working on the album's lyrics well into the recording of Nevermind. Additionally, Cobain's phrasing on the album is often difficult to understand. Vig asserted that clarity of Cobain's singing was not paramount. Vig said, "Even though you couldn't quite tell what he was singing about, you knew it was intense as hell."[6] Cobain later complained when rock journalists attempted to decipher his singing and extract meaning from his lyrics, writing: "Why in the hell do journalists insist on coming up with a second-rate Freudian evaluation of my lyrics, when 90 percent of the time they've transcribed them incorrectly?"[40]

Charles R. Cross asserted in his 2001 biography of Cobain, Heavier Than Heaven, that many of the songs written for Nevermind were about Cobain's dysfunctional relationship with Tobi Vail. After their relationship ended, Cobain began writing and painting violent scenes, many of which revealed a hatred for himself and others. Songs written during this period were less violent, but still reflected anger absent from Cobain's earlier songs. Cross wrote, "In the four months following their break-up, Kurt would write a half dozen of his most memorable songs, all of them about Tobi Vail." "Drain You" begins with the line, "One baby to another said 'I'm lucky to have met you,'" quoting what Vail had once told Cobain, and the line "It is now my duty to completely drain you" refers to the power Vail had over Cobain in their relationship. According to Novoselic, "'Lounge Act' is about Tobi," and the song contains the line "I'll arrest myself, I'll wear a shield," referring to Cobain having the K Records logo tattooed on his arm to impress Vail. Though "Lithium" had been written before Cobain knew Vail, the lyrics of the song were changed to reference her.[41] Cobain also said in an interview with Musician that "some of my very personal experiences, like breaking up with girlfriends and having bad relationships, feeling that death void that the person in the song is feeling—very lonely, sick".[42]

Title

The tentative title Sheep was something Cobain created as an inside joke directed towards the people he expected to buy the album. He wrote a fake advertisement for Sheep in his journal that read "Because you want to not; because everyone else is."[43] Novoselic said the inspiration for the title was the band's cynicism about the public's reaction to Operation Desert Storm.[17] As recording ended, Cobain grew tired of the title and suggested to Novoselic that the album be named Nevermind. Cobain liked the title because it was a metaphor for his attitude on life and because it was grammatically incorrect.[44]

"Nevermind" appears on the album liner notes as the last word in a paragraph of lyric fragments that ends with "I found it hard, it was hard to find, oh well, whatever, nevermind" from "Smells Like Teen Spirit".[45] The word "nevermind" also echoes the Sex Pistols' Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols, one of Cobain's favorite albums.[46]

Artwork

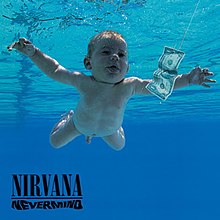

The album cover shows a naked baby boy swimming underwater with a U.S. dollar bill on a fishhook just out of his reach. According to Cobain, he conceived the idea while watching a television program on water births. Cobain mentioned it to Geffen's art director Robert Fisher. Fisher found some stock footage of underwater births, but they were too graphic for the record company to use. Furthermore, the stock house that controlled the photo of a swimming baby that they chose wanted $7,500 a year for its use. Instead, Fisher sent a photographer, Kirk Weddle, to a pool for babies to take pictures. Five shots resulted and the band settled on the image of four-month-old Spencer Elden, the son of a friend of Weddle.[47] Geffen was concerned that the infant's penis, visible in the photo, would cause offense, and prepared an alternate cover without it; they relented when Cobain said the only compromise he would accept would be a sticker covering the penis reading: "If you're offended by this, you must be a closet pedophile."[48] The cover has since been recognized as one of the most famous album covers in popular music.[49] A few months after the original baby shot, Weddle also photographed the entire band underwater for a promotional poster.[50]

The back cover features a photograph of a rubber monkey in front of a collage created by Cobain. The collage features photos of raw beef from a supermarket advertisement, images from Dante's Inferno, and pictures of diseased vaginas from Cobain's collection of medical photos. Cobain noted, "If you look real close, there is a picture of Kiss in the back standing on a slab of beef."[51] The album's liner notes contain no complete lyrics; instead, the liner contains random song lyrics and unused lyrical fragments that Cobain arranged into a poem.[52]

Spencer Elden lawsuits

In August 2021,[53] Elden filed a lawsuit against Weddle, Cobain's estate, Grohl and Novoselic, claiming that the use of his likeness on the album cover was made without his consent or that of his legal guardians, that it violated federal child pornography statutes,[54] and that it resulted in "lifelong damages".[55] Elden said that, by refusing to censor the artwork with a sticker, Nirvana had failed to protect him from child sexual exploitation.[56] The lawsuit also stated that "Cobain chose the image depicting Spencer—like a sex worker—grabbing for a dollar bill that is positioned dangling from a fishhook in front of his nude body with his penis explicitly displayed".[57][58]

Attorney Jamie White criticized the lawsuit as "frivolous" and "really offensive to the true victims" of child sexual abuse. Fordham Law School professor James Cohen said the context of the cover did not suggest pornography. White and Cohen concluded that Elden intended to make money with the lawsuit.[59] In December, lawyers for the defendants sought to dismiss the lawsuit, saying it was filed too late and that its claim that the image depicts sexual abuse was "not serious". They noted that Elden had "spent three decades profiting from his celebrity as the self-anointed 'Nirvana Baby'", having recreated the artwork several times, and that he had the album title tattooed on his chest. They argued that the cover instead "evokes themes of greed, innocence, and the motif of the cherub in western art".[60] After Elden's lawyers did not file an opposition, the lawsuit was dismissed by a judge on January 3, 2022, however the judge did allow for future lawsuits.[61]

Elden refiled again on January 14, 2022, amending the original suit by removing charges of child sex trafficking while arguing it was child pornography.[62] On September 2, 2022, a judge ruled against Elden saying he had waited too long to file the suit and cited a 10-year statute of limitations from the date the plaintiff becomes an adult at age 18, meaning Elden needed to file before he turned 28. In addition the judge blocked any additional filings in the future, bringing the case to a "final" close, although Spencer says he intends to appeal.[63]

Release

Nevermind was released on September 24, 1991. American record stores received an initial shipment of 46,251 copies,[64] while 35,000 copies were shipped in the United Kingdom, where Nirvana's first album Bleach had been successful.[65] The lead single "Smells Like Teen Spirit" had been released on September 10 with the intention of building a base among alternative rock fans, while the next single "Come as You Are" would possibly garner more attention.[66] Days before the release date, the band began a short American tour in support of the album. Geffen hoped that Nevermind would sell around 250,000 copies, matching sales of Sonic Youth's Geffen debut Goo.[67] The most optimistic estimate was that Nevermind could be certified gold (500,000 copies sold) by September 1992.[68]

Nevermind debuted on the Billboard 200 at number 144.[69] Geffen shipped about half of the initial U.S. pressing to the American Northwest, where it sold out quickly and was unavailable for days. Geffen put production of all other albums on hold to fulfill demand in the region.[70] Over the next few months, sales increased significantly as "Smells Like Teen Spirit" unexpectedly became more and more popular. The song's video had received a world premiere on MTV's late-night alternative show 120 Minutes, and soon proved so popular that the channel began playing it during the day.[71] "Smells Like Teen Spirit" reached number six on the US Billboard Hot 100.[72] The album was soon certified gold, but the band was relatively uninterested. Novoselic recalled, "Yeah I was happy about it. It was pretty cool. It was kind of neat. But I don't give a shit about some kind of achievement like that. It's cool—I guess."[73]

As the band set out for their European tour at the start of November 1991, Nevermind entered the Billboard Top 40 for the first time at number 35. By this point, "Smells Like Teen Spirit" had become a hit and the album was selling so fast none of Geffen's marketing strategies could be enacted. Geffen president Ed Rosenblatt told The New York Times, "We didn't do anything. It was just one of those 'Get out of the way and duck' records."[74] Nirvana found as they toured Europe during the end of 1991 that the shows were dangerously oversold, television crews became a constant presence onstage, and "Smells Like Teen Spirit" was almost omnipresent on radio and music television.[75]

Nevermind became Nirvana's first number-one album on January 11, 1992, replacing Michael Jackson's Dangerous at the top of the Billboard charts. By this time, Nevermind was selling approximately 300,000 copies a week.[76][77] It returned for a second week at number one in February.[78] "Come as You Are" was released as the second single in March 1992; it reached number nine on the UK Singles Chart and number 32 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.[79] Two more singles, "Lithium" and "In Bloom", reached number 11 and 28 on the UK Singles Chart.[80]

Nevermind was certified gold and platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in November 1991 and certified Diamond in March 1999.[81] It was also certified Diamond in Canada (1,000,000 units sold) by the Canadian Recording Industry Association in March 2001[82] and six times platinum in the United Kingdom.[83] It has gone on to sell more than 30 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling albums of all time.[84]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[86] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 9/10[88] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Select | 4/5[91] |

| The Village Voice | A−[92] |

Geffen's press promotion for Nevermind was lower than that typical of a major record label. The label's publicist primarily targeted music publications with long lead times for publication as well as magazines in the Seattle area. The unexpectedly positive feedback from critics who had received the album convinced the label to consider increasing the album's original print run.[65]

At first, Nevermind did not receive many reviews, and many publications ignored the album. Months after its release and after "Smells Like Teen Spirit" garnered airplay, print media organizations were "scrambling" to cover the phenomenon the album had become. However, by that point, much of the attention fell on Cobain rather than the album itself. The reviews that did initially appear were largely positive.[93] Karen Schoemer of The New York Times wrote, "With 'Nevermind,' Nirvana has certainly succeeded. There are enough intriguing textures, mood shifts, instrumental snippets and inventive word plays to provide for hours of entertainment." Schoemer concluded, "'Nevermind' is more sophisticated and carefully produced than anything peer bands like Dinosaur Jr. and Mudhoney have yet offered."[94]

Entertainment Weekly gave Nevermind an A− rating, and reviewer David Browne argued that on Nevermind, Nirvana "never entertain the notion" of wanting to sound "normal", compared to other contemporary alternative bands.[86] Concluding his enthusiastic review for the British Melody Maker, Everett True wrote that "When Nirvana released Bleach all those years ago, the more sussed among us figured they had the potential to make an album that would blow every other contender away. My God have they proved us right."[95] Spin gave Nevermind a favorable review stating that "you'll be humming all the songs for the rest of your life—or at least until your CD-tape-album wears out."[96] Select compared the band to Jane's Addiction, Sonic Youth, and the Pixies, stating that the album "proves that Nirvana truly belong in such high company."[91] Rolling Stone gave the album three out of five stars. Reviewer Ira Robbins wrote, "If Nirvana isn't onto anything altogether new, Nevermind does possess the songs, character and confident spirit to be much more than a reformulation of college radio's high-octane hits."[90]

Some of the reviews were not entirely positive. The Boston Globe was less enthusiastic about the album; reviewer Steve Morse wrote, "Most of Nevermind is packed with generic punk-pop that had been done by countless acts from Iggy Pop to the Red Hot Chili Peppers," and added "the band has little or nothing to say, settling for moronic ramblings by singer-lyricist Cobain."[97]

Nevermind was voted the best album of the year in The Village Voice Pazz & Jop critics' poll; "Smells Like Teen Spirit" also topped the single of the year and video of the year polls.[98] Nevermind topped the poll by a large majority, and Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote in his companion piece to the poll, "As a modest pop surprise they might have scored a modest victory, like De La Soul in 1990. Instead, their multi-platinum takeover constituted the first full-scale public validation of the Amerindie values—the noise, the toons, the 'tude—the radder half of the [Pazz & Jop poll] electorate came up on."[99] In the United Kingdom, the album was ranked number one on NME's Best Fifty LPs of 1991.[100] The album garnered the band three Grammy Award nominations in total at the 34th and 35th Grammy Awards.[101] Among the nominations was the Best Alternative Music Album award.[101]

Legacy

Nevermind popularized the Seattle grunge movement and brought alternative rock as a whole into the mainstream, establishing its commercial and cultural viability[102] and leading to an alternative rock boom in the music industry.[103] Though a short tenure from the album's release to the death of Cobain, the album's and singles' success propelled Nirvana to being regarded by the media as the biggest band in the world — especially throughout 1992.[104] As a grunge act, the band's success over the popular hair metal acts of the time drew similarities to the early 1960s British Invasion of American popular music.[35] The album also initiated a resurgence of interest in punk culture among teenagers and young adults of Generation X.[105] Journalist Chuck Eddy cited Nevermind's release as roughly the end of the "high album era".[106]

Billboard writer William Goodman lauds the album, particularly in comparison to the music and image of hair metal acts: "Instead of the chest-beating, coke-blowing, women-objectifying macho rock star of the ’80s, Cobain popularized (or re-invigorated) the image of the sensitive artist, the pro-feminism, anti-authoritarian smart alec punk with a sweet smile and gentle soul."[39] In its citation placing it at number 17 in its 2003 list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, Rolling Stone said, "No album in recent history had such an overpowering impact on a generation—a nation of teens suddenly turned punk—and such a catastrophic effect on its main creator."[107] Gary Gersh, who signed Nirvana to Geffen Records, added that "There is a pre-Nirvana and post-Nirvana record business...'Nevermind' showed that this wasn't some alternative thing happening off in a corner, and then back to reality. This is reality."[108]

The album sparked a global cultural revolution, especially towards youth around the world. Goodman says that Nevermind "killed off hair metal, and sparked a cultural revolution across the globe".[39] Speaking to the BBC, Brazilian cultural studies academic Moyses Pinto stated that he was struck by Nevermind, saying "I thought: 'this is perfect'; it sounded like a bright synthesis of noise and pop music."[109] In similar praise, Neto says that the impact of Nirvana, as well as MTV, during the time of Nevermind, caused a new youth who listened to the same music and dressed similarly (grunge fashion). Neto further remarks that "there was a cultural homogeneity probably never experienced before" and that "grunge culture became dominant very quickly; all that had been 'cool' suddenly became ugly and exaggerated, and Kurt [Cobain] was the symbol of transgression."[109] Michael Azerrad argued in his Nirvana biography Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana (1993) that Nevermind marked an epochal generational shift in music similar to the rock-and-roll explosion in the 1950s and the end of the dominance of the baby boomer generation on popular music. Azerrad wrote, "Nevermind came along at exactly the right time. This was music by, for, and about a whole new group of young people who had been overlooked, ignored, or condescended to."[110]

The success of Nevermind surprised Nirvana's contemporaries, who felt dwarfed by its influence. Fugazi frontman Guy Picciotto later said: "It was like our record could have been a hobo pissing in the forest for the amount of impact it had ... It felt like we were playing ukuleles all of a sudden because of the disparity of the impact of what they did."[111] Karen Schoemer of the New York Times wrote that "What's unusual about Nirvana's Nevermind is that it caters to neither a mainstream audience nor the indie rock fans who supported the group's debut album."[112] In 1992, Jon Pareles of The New York Times described the aftermath of the album's breakthrough: "Suddenly, all bets are off. No one has the inside track on which of dozens, perhaps hundreds, of ornery, obstreperous, unkempt bands might next appeal to the mall-walking millions." Record company executives offered large advances and record deals to bands, and replaced their previous strategies of building audiences for alternative bands with the attempts to achieve mainstream popularity quickly.[113]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | A[115] |

| Blender | |

| Christgau's Consumer Guide | A[117] |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[119] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | |

Nevermind has continued to garner critical praise, has been ranked highly on lists of the most acclaimed albums of all time and is ranked the best album of the 1990s according to Acclaimed Music which statistically aggregates hundreds of published lists.[124] The album was ranked number 17 on Rolling Stone's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[107] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revised list,[125] and upgrading to number 6 in 2020 revised list.[126] In 2019, Rolling Stone also ranked Nevermind number one on its list of the 100 Best Albums of the '90s, calling it the "album that guaranteed the nineties would not suck."[127] Also in 2019, Nevermind was ranked number one on Rolling Stone's 50 Greatest Grunge Albums list.[128] The magazine ranked the album number 10 in its list of 40 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time too.[129] In 2001, VH1 conducted a poll of more than 500 journalists, music executives and artists which judged Nevermind the second-best album in rock 'n' roll history, behind the Beatles' Revolver.[130] Time placed Nevermind, which writer Josh Tyrangiel called "the finest album of the 90s", on its 2006 list of "The All-TIME 100 Albums".[131] Pitchfork named the album the sixth best of the decade, noting that "anyone who hates this record today is just trying to be cool, and needs to be trying harder."[132] In 2004, the Library of Congress added Nevermind to the National Recording Registry, which collects "culturally, historically or aesthetically important" sound recordings from the 20th century.[133] On the other hand, Nevermind was voted the "Most Overrated Album in the World" in a 2005 BBC public poll.[134] In 2006, readers of Guitar World ranked Nevermind 8th on a list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Recordings.[135] Entertainment Weekly named it the 10th best album of all time on their 2013 list.[136] It was voted number 17 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[137] Christgau named it among his 10 best albums from the 1990s and said in retrospect it is an A-plus album.[138] In 2017, "Smells Like Teen Spirit" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.[139]

Reissues

In 1996, Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs released Nevermind on vinyl as part of its ANADISQ 200 series, and as a 24-karat gold CD. The CD pressings included "Endless, Nameless". The LP version quickly sold out its limited pressing but the CD edition stayed in print for years.[140] In 2009, Original Recordings Group released Nevermind on limited edition 180g blue vinyl and regular 180g black vinyl mastered and cut by Bernie Grundman from the original analog tapes.[141]

In September 2011, the album's 20th anniversary, Universal Music Enterprises reissued Nevermind in a two-CD "deluxe edition" and a four-CD/one-DVD "Super Deluxe Edition".[142] The first disc on both editions features the original album with studio and live B-sides. The second discs feature early session recordings, including the Smart Studio sessions and some band rehearsals recorded with a boombox, plus two BBC session recordings. The "Super Deluxe Edition" also includes Vig's original mix of the album and CD and DVD versions of Live at the Paramount. IFPI reported that as of 2012, the 20th anniversary formats of the album that were released in 2011 had sold nearly 800,000 units.[143] In June 2021, Novoselic revealed that he and Grohl were compiling the 30th-anniversary edition of the album.[144][145][146] In September 2021, it was announced that BBC Two in the United Kingdom would celebrate the 30th anniversary with a documentary titled When Nirvana Came to Britain, which featured contributions from Noveselic and Grohl.[147] That same month, a 30th-anniversary edition of Nevermind was announced, which became available in eight-LP and five-CD editions and contained 70 previously unreleased live songs.[148]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Kurt Cobain, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Smells Like Teen Spirit" | Cobain, Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl | 5:01 |

| 2. | "In Bloom" | 4:14 | |

| 3. | "Come as You Are" | 3:39 | |

| 4. | "Breed" | 3:03 | |

| 5. | "Lithium" | 4:17 | |

| 6. | "Polly" | 2:57 | |

| 7. | "Territorial Pissings" | Cobain, Chet Powers | 2:22 |

| 8. | "Drain You" | 3:43 | |

| 9. | "Lounge Act" | 2:36 | |

| 10. | "Stay Away" | 3:32 | |

| 11. | "On a Plain" | 3:16 | |

| 12. | "Something in the Way" | 3:52 | |

| 13. | "Endless, Nameless" (hidden track on later CD pressings) | Cobain, Novoselic, Grohl | 6:43 |

| Total length: | 49:07 | ||

Notes

- After the initial pressing, CD versions included "Endless, Nameless" as a hidden track which begins after 10 minutes of silence following "Something in the Way", making track 12's total length 20:35. The song is not included on vinyl versions.

Personnel

|

Nirvana

Additional musicians

|

Technical staff and artwork

|

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

Decade-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[289] | 3× Platinum | 180,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[290] | 5× Platinum | 350,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[291] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[292] | 8× Platinum | 400,000 |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[293] | Platinum | 250,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[294] | Diamond | 1,000,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[295] | 6× Platinum | 120,000 |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[296] | Gold | 46,830[296] |

| France (SNEP)[297] | Diamond | 1,000,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[298] | 2× Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[299] sales since 2009 |

3× Platinum | 150,000 |

| Japan (RIAJ)[300] | 3× Platinum | 600,000^ |

| Mexico (AMPROFON)[301] | 2× Gold | 200,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[302] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[303] | 7× Platinum | 105,000^ |

| Poland (ZPAV)[304] BMG release |

Platinum | 100,000* |

| Poland (ZPAV)[305] Geffen/Universal Music release |

3× Platinum | 60,000 |

| Portugal (AFP)[306] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| Singapore | — | 35,000[307] |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[308] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[309] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[310] | Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[311] | 6× Platinum | 1,800,000 |

| United States (RIAA)[312] | Diamond | 10,640,000[313][314] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

- 1991 in music

- Album era

- Classic Albums: Nirvana – Nevermind

- Nevermind It's an Interview

- List of best-selling albums

- List of best-selling albums in Belgium

- List of best-selling albums in France

- List of best-selling albums in the United States

- List of diamond-certified albums in Canada

- Off the Deep End

- List of 200 Definitive Albums in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Notes

- "Nevermind sessions".

- "This Day in Music Spotlight: Nirvana Begins Recording 'Nevermind'". .gibson.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- Borzillo-Vrenna, Carrie (2003). Nirvana - The Day to Day Illustrated Journals (1st ed.). Barnes & Noble. p. 71. ISBN 0-7607-4893-4.

- "Nirvana, 'Nevermind (30th Anniversary Edition)': Album Review".

- School, GABRIELLE ZEVIN, Spanish River High. "NIRVANA'S 'NEVERMIND' UNCONVENTIONAL HEAVY METAL". Sun-Sentinel.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Classic Albums—Nirvana: Nevermind [DVD]. Isis Productions, 2004.

- Hoi, Tobias. "In Bloom". Guitar World. October 2001.

- "Live Nirvana – Sessions History – Studio Sessions – April 2–6, 1990 – Studio A, Smart Studios, Madison, WI, US". www.livenirvana.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 29

- Azerrad, 1993. p. 137

- Club Underground Show Flyer Live Nirvana [permanent dead link]

- WORT

- "Nirvana Live Guide – 1990". www.nirvanaguide.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2006. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- Azerrad, 1993. p. 138

- Azerrad, 1993. p. 162

- Azerrad, 1993. p. 164–65

- Cross, Charles R. "Requiem for a Dream". Guitar World. October 2001.

- Sandford 1995, p. 181

- Azerrad 1993, p. 167

- Azerrad 1993, p. 169

- Azerrad 1993, p. 174

- Azerrad 1993, p. 176

- di Perna, Alan. "Grunge Music: The Making of Nevermind". Guitar World. Fall 1996.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 96

- Azerrad 1993, p. 179–80

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 99

- Walls, Seth Colter (September 27, 2011). "Kurt Cobain Thought Nevermind Was Nirvana's Worst Album". Slate. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 102

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 103

- Azerrad, 1993. p. 145

- Lewis, Luke. "Nirvana – Nevermind". Q: Nirvana and the Story of Grunge. December 2005.

- di Perna, Alan. "Absolutely Foobulous!" Guitar World. August 1997.

- "Cobainspotting". Guitar World. October 2001.

- "Nirvana Producer Butch Vig Remembers 'Nevermind'". Billboard. September 20, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- Sheppherd, Josh (2004). ""Nevermind"—Nirvana (1991)" (PDF). Library of Congress.

- Jovetic, Mirjana (October 27, 2000). "Rewind to 1991". South China Morning Post. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- "Nirvana's "Nevermind" Made, and Unmade, Alternative Culture". The New Yorker. November 20, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- "Nirvana: The stories behind every song on Nevermind". Kerrang!. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- Goodman, William (September 23, 2016). "Nirvana's 'Nevermind' Turns 25: Classic Track-by-Track Review". Billboard. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- Cross 2001, p. 182

- Cross 2001, p. 168–69

- Morris, Chris. "The Year's Hottest Band Can't Stand Still." Musician, January 1992.

- Cross 2001, p. 154

- Cross 2001, p. 189

- "Did Nirvana 'copy' Sex Pistols' Never Mind The Bollocks album title with their Nevermind album?". Radio X. October 28, 2019. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Keeble, Edward (January 22, 2014). "Hand-Written List of Kurt Cobain's Favourite Albums is Revealed Online". gigwise.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Bachor, Kenneth (September 23, 2016). "The Baby From Nirvana's Nevermind Is 25 Now". Time. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017.

- Azerrad 1993, p. 180–81

- "Readers Poll: The Best Album Covers of All Time". Rolling Stone. June 15, 2011. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Jonze, Tim (June 6, 2019). "Kirk Weddle's best photograph: Nirvana's Nevermind swimming baby". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 108

- Azerrad 1993, p. 209

- "Spencer Elden, the baby from Nirvana's Nevermind album cover, sues alleging child exploitation". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. August 25, 2021. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- Gray, Geordie (August 25, 2020). "Nirvana sued by the baby from 'Nevermind' for child pornography". Tone Deaf. Brag Media. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- Minsker, Evan (August 24, 2021). "Nirvana Sued by Baby From Nevermind Album Artwork for Child Pornography". Pitchfork. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- DeVille, Chris (August 24, 2020). "The Nevermind Baby Sues Nirvana, Calling The Album Cover Child Pornography". Stereogum. Scott Lapatine. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Man Photographed as Baby on 'Nevermind' Cover Sues Nirvana, Alleging Child Pornography". www.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Elden vs Nirvana Complaint". www.documentcloud.org. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Legal experts trash 'child porn' claim over Nirvana 'Nevermind' album cover". New York Post. August 26, 2021. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (December 24, 2021). "Nirvana seek to dismiss sexual abuse lawsuit concerning Nevermind cover". The Guardian. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- "Nirvana Nevermind baby cover artwork lawsuit dismissed". The Guardian. January 4, 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Nirvana baby refiles lawsuit over Nevermind album cover". BBC News. January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- Kreps, Daniel (September 3, 2022). "Nirvana Wins 'Nevermind' Baby Lawsuit as Judge Dismisses Case for Final Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Azerrad 1993, p. 196

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 113

- Azerrad 1993, p. 227

- Wice, Nathaniel. "How Nirvana Made It". Spin. April 1992.

- Azerrad 1993, p. 193

- Azerrad 1993, p. 198

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 119

- Azerrad 1993, p. 199

- "The Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- Azerrad 1993, p. 202

- Azerrad 1993, p. 228

- Azerrad 1993, p. 203

- Azerrad 1993, p. 229

- "The Pop Life; Nirvana's 'Nevermind' Is No. 1". The New York Times. January 8, 1992. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- "January 11, 1992". Billboard 200.

- Nirvana – Awards Archived December 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". AllMusic. Retrieved on 14 July 2013.

- "Nirvana – Artist Chart History Archived October 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". Official Chart Company. Retrieved on 14 July 2013.

- RIAA Searchable Database Archived June 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. RIAA.com. Retrieved on March 10, 2007. NB user needs to enter "Nirvana" in "Artist" and click "search".

- Gold & Platinum – March 2001 Archived October 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. CRIA.ca. March 2001. Retrieved on September 27, 2007.

- Certified Award Search – Nirvana – Nevermind Archived January 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved on August 3, 2011. NB user needs to enter "Nirvana" in the field "Search", select "Artist" in the field "Search by", and click "Go"."Unknown". Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- "Friday essay: Nevermind 30 years on – how Nirvana's second album tilted the world on its axis".

- Kot, Greg (October 10, 1991). "Nirvana: Nevermind (DGC)". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- Browne, David (October 25, 1991). "Nirvana's 'Nevermind': EW Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- Gold, Jonathan (October 6, 1991). "Power Trio, Pop Craft". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- Lamacq, Steve (September 21, 1991). "Nirvana – Nevermind". NME. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- King, Sam (November 1991). "Nirvana: Nevermind". Q. No. 62. Archived from the original on May 19, 2000. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Robbins, Ira (November 28, 1991). "Nirvana: Nevermind". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- Perry, Andrew (October 1991). "Nirvana: Nevermind". Select. No. 16. p. 68.

- Christgau, Robert (November 5, 1991). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 116-117

- Schoemer, Karen. "Pop/Jazz; A Band That Deals In Apathy". The New York Times. September 27, 1991. Retrieved on September 27, 2007.

- True, Everett. Nirvana: The Biography. Da Capo Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-306-81554-6. p. 233.

- Spencer, Lauren (December 1991). "Nirvana: Nevermind". Spin. Vol. 7, no. 9. p. 112. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 117

- "The 1991 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. March 3, 1992. Archived from the original on August 4, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- Christgau, Robert (March 3, 1992). "Reality Used to Be a Friend of Ours". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on September 11, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- "NME's Fifty Best LPs of 1991". NME. December 21, 1991. p. 56. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- www.grammy.com https://www.grammy.com/artists/nirvana/8026. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Olsen, Eric. "10 years later, Cobain lives on in his music" Archived June 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. MSNBC April 9, 2004. Retrieved on September 27, 2007.

- Hogan, Marc (March 20, 2017). "Exit Music: How Radiohead's OK Computer Destroyed the Art-Pop Album in Order to Save It". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- "My Time with Kurt Cobain". The New Yorker. September 22, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- "How Nirvana Made 'Nevermind'". Rolling Stone. March 5, 2013. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Eddy, Chuck (2011). Rock and Roll Always Forgets: A Quarter Century of Music Criticism. Duke University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-82235010-1. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- 17: Nevermind – Nirvana Archived March 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved on February 12, 2012.

- Pareles, Jon (November 14, 1993). "Nirvana, the Band That Hates to Be Loved: The Band That Hates to Be Loved". The New York Times. ProQuest 109121712.

- Haider, Arwa. "Nevermind at 30: How the Nirvana album shook the world". www.bbc.com. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- Azerrad 1993, p. 225

- Azerrad, 2001. p. 493

- Schoemer, Karen (January 26, 1992). "The Art Behind Nirvana's Ascent to the Top: Not many bands come up from the underground to hit No. 1 as fast as this Seattle trio – or make so few musical concessions". The New York Times. ProQuest 108871606.

- Pareles, Jon. Pop View; Nirvana-bes Awaiting Fame's Call". The New York Times. June 14, 1992. Retrieved on June 3, 2008.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Nevermind – Nirvana". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Hyden, Steven (September 27, 2011). "Nirvana: Nevermind". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Wolk, Douglas (April 2008). "Nirvana: Nevermind". Blender. No. 68. p. 88. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Christgau, Robert (2000). "Nirvana: Nevermind". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 227. ISBN 0-312-24560-2. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- McCormick, Neil (September 22, 2011). "Nirvana: Nevermind (20th Anniversary Edition), CD review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Harvell, Jess (September 27, 2011). "Nirvana: Nevermind [20th Anniversary Edition]". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "Nirvana: Nevermind". Q. No. 303. October 2011. p. 133.

- Rosen, Jody (September 27, 2011). "Nevermind 20th Anniversary". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- Young, Charles M. (2004). "Nirvana". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 588–589. ISBN 0-743-20169-8.

- Dolan, Jon (August 2006). "How to Buy: Heavy Metal". Spin. Vol. 22, no. 8. p. 78. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "Acclaimed Music". www.acclaimedmusic.net. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- 1: Nevermind – Nirvana Archived August 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved on October 7, 2013.

- "50 Greatest Grunge Albums". Rolling Stone. April 1, 2019. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "40 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. April 6, 2016. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- "Beatles' 'Revolver' judged best album". Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Tyrangiel, Josh. "Nevermind by Nirvana" Archived March 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Time. November 13, 2006. Retrieved on September 29, 2007.

- "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s" Archived June 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Pitchfork.com. Retrieved on November 25, 2009.

- MTV News staff. "For The Record: Quick News On Gwen Stefani, Pharrell Williams, Ciara, 'Dimebag' Darrell, Nirvana, Shins & More" Archived December 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. MTV. April 6, 2005. Retrieved on July 16, 2009.

- "Most Overrated Album in the World". BBC 6 Music. 2005. Archived from the original on November 11, 2005. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "100 Greatest Guitar Albums". Guitar World. October 2006.

- "Music: 10 All-Time Greatest." Archived January 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 08-04-2013.

- Colin Larkin, ed. (2006). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 42. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- Christgau, Robert (May 19, 2021). "Xgau Sez: May, 2021". And It Don't Stop. Substack. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- "Nirvana". GRAMMY.com. November 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- Berkenstadt; Cross, p. 148–49

- "Nevermind and Original Recordings Group Archived December 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". Stereophile.com.

- "Deluxe Edition of Nirvana's Nevermind Coming Out This Year" Archived October 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. UpVenue.com. June 22, 2011. Retrieved on June 23, 2011.

- "New Nirvana footage helps drive interest" (PDF). Recording Industry In Numbers - The Recorded Music Market in 2011. IFPI. 2012. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- Richards, Will (June 16, 2021). "Nirvana's Krist Novoselic teases 'Nevermind' 30th anniversary reissue". NME. Archived from the original on June 19, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Carter, Emily (June 17, 2021). "Nirvana: Krist Novoselic hints at 30th anniversary reissue of Nevermind". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on June 19, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- "Nirvana Nevermind 30th Anniversary Album Review". Rabbit Hole Music. September 18, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- "BBC Music to mark 30 years since the release of Nirvana's Nevermind". BBC Online. September 3, 2021. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- Kreps, Daniel (September 23, 2021). "Nirvana Pack 'Nevermind' 30th-Anniversary Reissue With 4 Unreleased Concerts". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- "Australiancharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- "ARIA Top 20 Alternative Charts". ARIA Report. No. 105. January 26, 1992. p. 11. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- "Austriancharts.at – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Top Ten Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. February 22, 1992. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- "Top Ten Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. February 29, 1992. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- "Top RPM Albums: Issue 2071". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- "Top 10 Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. February 22, 1992. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "European Top 100 Albums" (PDF). Music & Media. April 11, 1992. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- Pennanen, Timo (2003). Sisältää hitin: levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 Archived July 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Otava Publishing Company Ltd. ISBN 951-1-21053-X.

- "InfoDisc : Le Détail des Albums de chaque Artiste" Archived September 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Infodisc.fr. Retrieved on October 14, 2012. NB user has to select "Nirvana" from the drop down list and click "OK".

- "Offiziellecharts.de – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- "Top Ten Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. March 7, 1992. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 1992. 19. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- "Top 10 Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. February 29, 1992. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- "Charts.nz – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Top 10 Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. October 10, 1992. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). "Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002" (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - "Swedishcharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Swisscharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Top 10 Sales in Europe" (PDF). Music & Media. February 15, 1992. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "Nirvana | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- Kimberley, Christopher (1998). Albums chart book: Zimbabwe. p. 46. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Ultratop.be – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Lista prodaje 18. tjedan 2021. (26.04.2021. - 02.05.2021.)" (in Croatian). Top Lista HR. May 9, 2021. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- "Ultratop.be – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Danishcharts.dk – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Nirvana: Nevermind" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Lescharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Nirvana – Greece Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "Italiancharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "ネヴァーマインド<スーパー・デラックス・エディション>" Archived December 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Oricon.co.jp. Retrieved on April 18, 2012.

- "Portuguesecharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- "Spanishcharts.com – Nirvana – Nevermind". Hung Medien. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Nirvana Official UK Charts History". officialcharts.com. Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- "Nirvana Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard.

- "RPM 100 Albums (CDs & Cassettes) of 1991". RPM. December 21, 1991. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- "Complete UK Year-End Album Charts". Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 1992". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- "Jahreshitparade 1992". Hung Medien (in German). Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "The RPM Top 100 Albums of 1992" (PDF). RPM. Vol. 56, no. 25. December 19, 1992. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1992" (in Dutch). dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- "1992 Year-End Sales Charts" (PDF). Music & Media. December 19, 1992. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- "Les Albums (CD) de 1992 par InfoDisc". InfoDisc (in French). Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts". GfK Entertainment (in German). offiziellecharts.de. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- "Top Selling Albums of 1992". Recorded Music NZ. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1992" (ASP). Hung Medien (in German). Swiss Music Charts. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Billboard 200 Albums - Year-End 1992". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on November 3, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- "Top 100 Albums 1993" (PDF). Music Week. January 15, 1994. p. 25. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "The ARIA Australian Top 100 Albums 1994". Australian Record Industry Association Ltd. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1994" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- "Najlepiej sprzedające się albumy w W.Brytanii w 1994r" (in Polish). Z archiwum...rocka. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- "1994: Billboard 200 Albums". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on May 6, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 1995". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- "Rapports annueles 1995" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 62, No. 20, December 18 1995". RPM. December 18, 1995. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1995". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- "1995: Billboard 200 Albums". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 1996". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- "Najlepiej sprzedające się albumy w W.Brytanii w 1998r" (in Polish). Z archiwum...rocka. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- "Najlepiej sprzedające się albumy w W.Brytanii w 1999r" (in Polish). Z archiwum...rocka. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- "The Official UK Albums Chart 2001" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- "Canada's Top 200 Alternative albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 2, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- "Top 100 Metal Albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on August 12, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- "UK Year-End Charts 2002" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2005 - Mid price" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Rapports Annuels 2005 - Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "The Official UK Albums Chart - Year-End 2005" (PDF). UKchartsplus.co.uk. Official Charts Company. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2006 - Mid price" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Rapports Annuels 2006 - Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Rapports Annuels 2009 – Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2011 - Mid price" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Rapports Annuels 2011 - Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Top 100 – annual chart – 2011". Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- "Classifiche annuali Fimi-GfK: Vasco Rossi con "Vivere o Niente" e' stato l'album piu' venduto nel 2011" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. January 16, 2012. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2021. Click on "Scarica allegato" to download the zipped file containing the year-end chart files.

- The Official Top 40 biggest selling vinyl albums and singles of 2012 Archived January 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine officialcharts.com. January 23, 2012.

- "End of Year Charts: 2011" (PDF). UKChartsPlus. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2012 - Mid price" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Rapports Annuels 2012 - Mid price" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "El álbum más vendido durante 2013 en Argentina: "Violetta – Hoy somos más"" (in Spanish). Argentine Chamber of Phonograms and Videograms Producers. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- "ARIA Charts – End of Year Charts – Top 100 Albums 2015". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- "Classifiche "Top of the Music" 2015 FIMI-GfK: La musica italiana in vetta negli album e nei singoli digitali" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- Official Biggest Vinyl Singles and Albums of 2015 revealed Archived January 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine officialcharts.com. January 13, 2016.

- "Top of the Music – FIMI/GfK: Le uniche classifiche annuali complete" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "W 2016 roku najlepiej sprzedającym się albumem było "Życie po śmierci" O.S.T.R." 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- The Official Top 40 biggest selling vinyl albums and singles of 2016 Archived January 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine officialcharts.com. January 1, 2017.

- "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2016". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on December 8, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- "Jahreshitparade Alben 2017" (in German). austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- "Classifica annuale 2017 (dal 30.12.2016 al 28.12.2017)" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on February 5, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- The Official Top 40 biggest selling vinyl albums and singles of 2017 Archived January 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine officialcharts.com. January 10, 2018.

- "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- "2018 ARIA Vinyl Albums Chart". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Ö3 Austria Top 40 Jahrescharts 2018: Longplay". Ö3 Austria Top 40. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- "Classifiche Annuali Top of the Music FIMI/GfK 2018: Protagonista La Musica Italiana" (Download the attachment and open the albums file) (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. January 7, 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- "TOP AFP 2018" (PDF). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa (in Portuguese). Audiogest. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "The Official Top 40 biggest vinyl albums and singles of 2018". officialcharts.com. Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2018". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- "2019 ARIA Vinyl Albums Chart". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2019". Ultratop. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "Rapports Annuels 2019". Ultratop. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- "Top of the Music FIMI/GfK 2019: Un anno con la musica Italiana" (Download the attachment and open the Album file) (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- "Top AFP – Audiogest – Top 3000 Singles + EPs Digitais" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Associação Fonográfica Portuguesa. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- "The Official Top 40 biggest vinyl albums and singles of 2019". officialcharts.com. January 2, 2020. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2019". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2019". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- "2020 ARIA Vinyl Albums Chart". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- "Jahreshitparade Alben 2020" (in German). austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2020". Ultratop. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- "Rapports Annuels 2020". Ultratop. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- "Top Of The Music 2020: 'Persona' Di Marracash È L'album Piú Venduto" (Download the attachment and open the albums file) (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. January 7, 2021. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- "The Official Top 40 biggest vinyl albums and singles of 2020". officialcharts.com. January 6, 2021. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2020". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2020". Billboard. January 2, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- "2021 ARIA Vinyl Albums Chart". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- "Jahreshitparade Alben 2021" (in German). austriancharts.at. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2021" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- "Rapports annuels 2021" (in French). Ultratop. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts 2021" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- "Classifica annuale 2021 (dal 01.01.2021 al 30.12.2021)" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- "Top Selling Albums of 2021". Recorded Music NZ. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- "sanah podbija sprzedaż fizyczną w Polsce" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- "Top 100 Álbuns - Semanas 1 a 52 – De 01/01/2021 a 30/12/2021" (PDF). Audiogest (in Portuguese). p. 1. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2021". Official Charts Company. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2021". Billboard. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- "Catalog Albums – Year-End 2021". Billboard. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- "Top Rock Albums – Year-End 2021". Billboard. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- IFPI) Brandle, Lars (March 1, 2022). "Adele's '30' Dominates IFPI's 2021 Album Charts". Billboard. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- Mayfield, Geoff (December 25, 1999). "1999 The Year in Music Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade – The listing of Top Pop Albums of the '90s & Hot 100 Singles of the '90s"". Billboard. p. YE-20. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via Google Books.

- "Official Top 100 biggest selling vinyl albums of the decade". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 1996 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- "Austrian album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in German). IFPI Austria.

- "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2022". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved August 30, 2022.

- "Brazilian album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil.

- "Canadian album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind". Music Canada.

- "Danish album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- "Nirvana" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- "French album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Nirvana; 'Nevermind')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- "Italian album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- "Japanese album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved October 15, 2011. Select 2002年11月 on the drop-down menu

- "Certificaciones" (in Spanish). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Type Nirvana in the box under the ARTISTA column heading and Nevermind in the box under the TÍTULO column heading.

- "Dutch album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Enter Nevermind in the "Artiest of titel" box.

- "New Zealand album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind". Recorded Music NZ.

- "Wyróżnienia – Platynowe płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 1999 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. September 22, 1999.

- "Wyróżnienia – Platynowe płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 2022 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. November 9, 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- "TOP OFICIAL AFP – Semana 40 de 2011" (in Portuguese). Artistas & Espectáculos. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011.

- Cheah, Philip (August 21, 1993). "Singapore" (PDF). American Radio History (Billboard Archive). p. SE-26. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Solo Exitos 1959–2002 Ano A Ano: Certificados 1991–1995. Solo Exitos 1959–2002 Ano A Ano. 2005. ISBN 84-8048-639-2. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2011.

- "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Nirvana; 'Nevermind')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- "British album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind". British Phonographic Industry.

- "American album certifications – Nirvana – Nevermind". Recording Industry Association of America.

- David, Barry (February 18, 2003). "Shania, Backstreet, Britney, Eminem And Janet Top All Time Sellers". Bertelsmann Music Group. New York: Music Industry News Network. Archived from the original on July 3, 2003. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- Rutherford, Kevin (September 23, 2016). "Nirvana's 'Nevermind': 9 Chart Facts About the Iconic Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

References

- Classic Albums—Nirvana: Nevermind [DVD]. Isis Productions, 2004.

- Azerrad, Michael. Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday, 1993. ISBN 0-385-47199-8

- Berkenstadt, Jim; Cross, Charles. Classic Rock Albums: Nevermind. Schirmer, 1998. ISBN 0-02-864775-0